Excavations at Heslerton,

By DOMINIC POWLESLAND, with CHRISTINE HAUGHTON and JOHN HANSON

The Archaeological Journal,

1986, Volume 143, pages 53-173

This report describes the excavation of a 4 hectare multi-period site

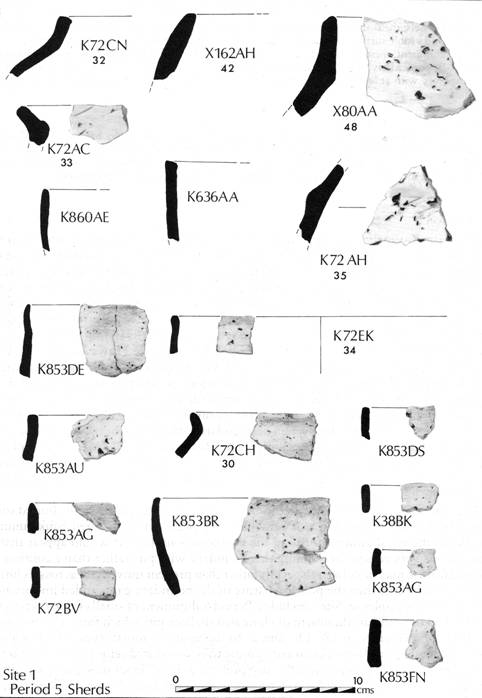

situated in the parish of Heslerton, North Yorkshire, on the southern edge of

the Vale of

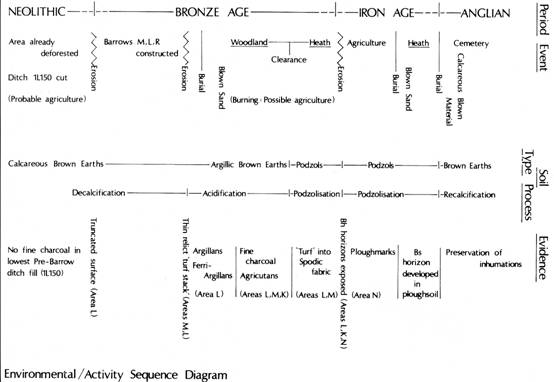

Occupation at the site began during the late Mesolithic with a flint

knapping area, which was also used during the Neolithic and early Bronze Age.

During the Late Neolithic a series of shallow gullies may represent the first

attempts to establish a field system, and domestic activity may be indicated by

two pairs of refuse pits. Other pits of this period demonstrate the presence of

an ill-defined avenue of very large post pits running across part of the site.

During the early Bronze Age two barrow cemeteries were present. The excavation

of

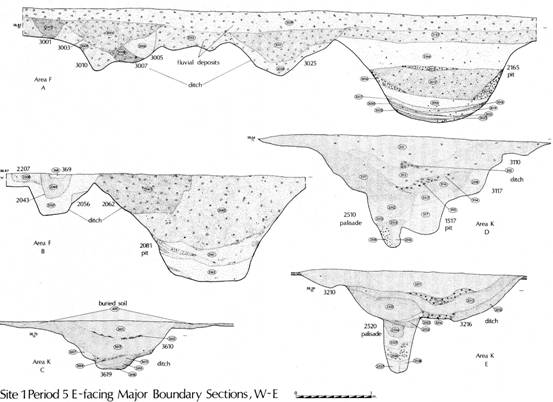

After the barrow cemeteries went out of use, woodland regenerated in the

area prior to the late Bronze and early Iron age, when the central part of the

site became the setting for extensive occupation dispersed along the line of a

major boundary which, once established, continued to function, though on a

lessening scale, throughout the Roman period when much of the site was turned

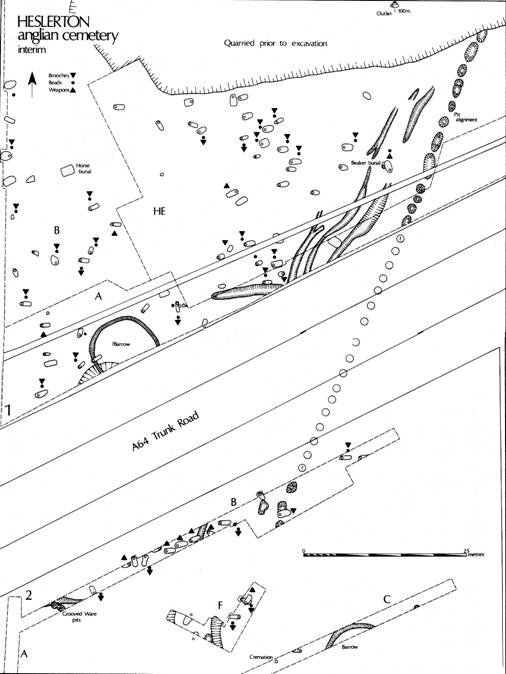

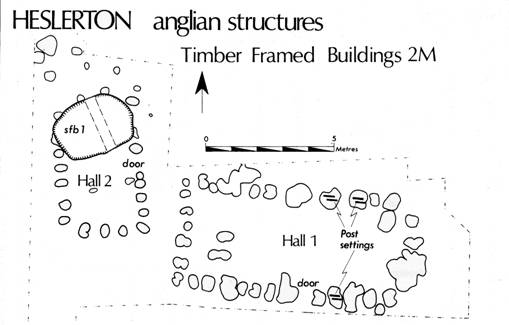

over to agriculture. During the early Anglo-Saxon period a cemetery was

established, focused upon

Note: This report has been prepared along the lines recommended by the Cunliffe Report (DOE 1975) and is divided into the printed report comprising of a description of all major contexts, their relationships and the artefactual and other evidence, with the principal periods of activity presented in eight chronological phases, labelled Periods 0 to 8; and the microfiche containing full specialist reports and supporting documentation. The complete archive from Site 1 is available for study by arrangement with Malton Museum.

INTRODUCTION

PROJECT STRATEGY

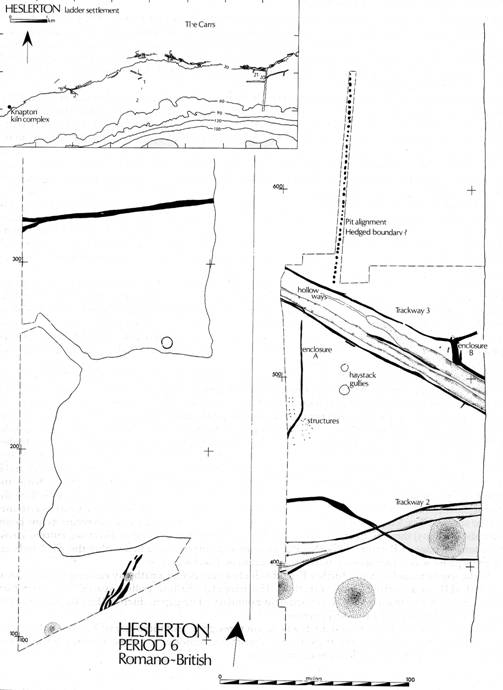

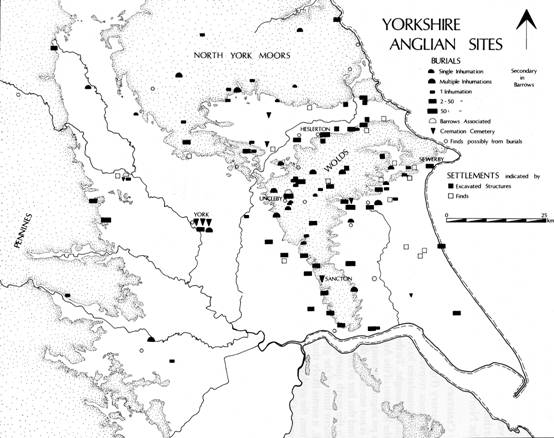

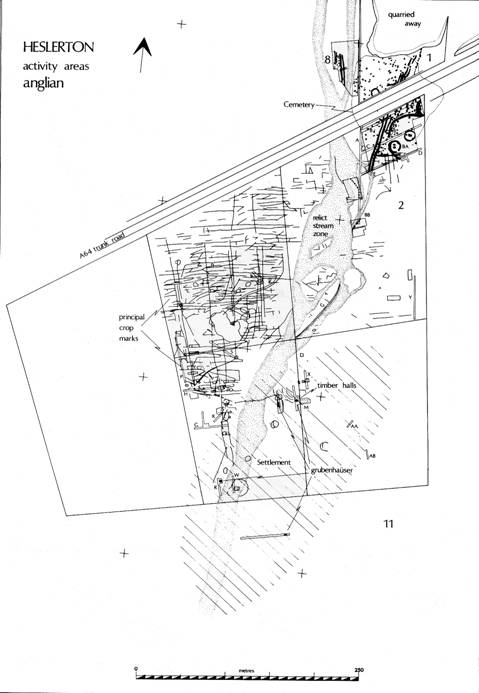

This report is the first of two covering rescue excavations carried out in the parish of Heslerton, in North Yorkshire, between 1977 and 1982. The Heslerton Parish Project was established in 1980 to provide an academic, framework against which to set the results of the excavations in an area of underestimated potential. The project area spans the interface between two distinct zones (Figure 1); in the south the scarp face of the Yorkshire Wolds rises to over 200m OD before gently sloping down into the Great Wold Valley whilst to the north the area is bounded by the River Derwent at the centre of the broad flat plain of the Vale of Pickering.

Figure 1 The Topography of Eastern Yorkshire

The position of eastern Yorkshire in the archaeology of the British Isles and northern Europe has long been established; the work of Greenwell (1877) and Mortimer (1905) has illustrated the wealth of its field monuments, but it is clear that the special place afforded eastern Yorkshire is largely based on the investigation of a single type of monument, the barrow, and also that the evidence is exclusively derived from the two upland areas in the region. On the chalk uplands, the Yorkshire Wolds included a large number of upstanding monuments, principally barrows and linear earthworks, which have frequently survived as modern boundaries. In the north of the region the North York Moors are similar, and it is easy to see why antiquarians and archaeologists have focused their attention on them. In contrast, the Vale of Pickering, separating these regions, has few upstanding monuments and in the past has been considered an area of very low potential, appearing on most distribution maps as a blank. Given that the distribution of barrows on the uplands indicates the presence of a large population in the area, the extent of the non-sepulchral database is minimal; what is perhaps more disturbing is that the work of Mortimer, Manby and others indicates that the Wolds, for the most part, become so badly denuded that only in exceptional conditions is there any likelihood of finding extensive domestic deposits that have survived erosion or destruction.

Excavations in the Vale of Pickering at Staxton and Sherburn by T. C. M. Brewster (1957, 1952) indicated that extensive aeolian deposits had preserved old land surfaces to an exceptional degree. The chance discovery in 1977 of Anglian metalwork, whilst stripping overburden at Cook's Sand Quarry, West Heslerton, led to a salvage excavation, undertaken by J. S. Dent (area 1HE, Figure 6b) followed by a small scale rescue excavation by the author in 1978 and 1979 (areas 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D). The results of this work coupled with limited air photographic survey in the area indicated that the southern margins of the Vale not only contain very extensive archaeological deposits, but also that in places they were well preserved as a result of capping layers of aeolian sands derived from the sandy deposits in the centre of the Vale. The uniformity of the geology, topography and the nature and extent of the archaeological deposits indicated from the air suggested that the examination of the Heslerton area could provide a representative archaeological sample of an extensive landscape incorporating the whole of the southern edge of the Vale and the northern margins of the Wolds. The strategy was designed to transcend the restraints imposed by concentration on features or sites of any particular type or period, focusing instead on a landscape approach.

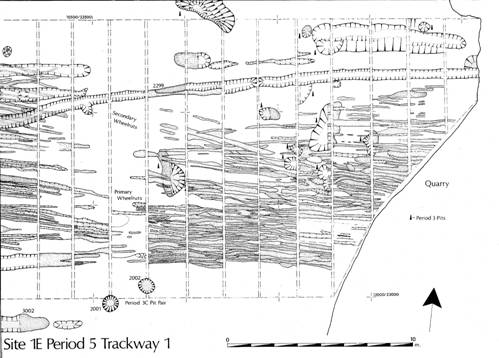

A parish transect was established running perpendicular to the geological, topographical, and environmental zones present which not only provided a means of presenting and isolating areas of particular potential but was also seen as a useful tool for the interpretation of the results of field-work (Figure 4).

The project, covering an 8 by 10 km area, includes the whole of Yedingham and Heslerton parishes together with parts of Sherburn to the east, Knapton to the west, East and West Lutton to the south, and Ebberston to the north, incorporating the parish boundaries. Since there is considerable uniformity in the parish morphology (Figure 2) both to the north and south of the Derwent, a detailed study of a single parish central to either group ought to provide a data base that is relevant to the group as a whole. The Vale has the potential to produce well-preserved and stratified sites, and it is possible that a detailed approach to part of the Vale will provide the necessary contexual data to enable the important body of evidence from the Wolds or the Moors to be set in a broader framework.

Figure 2 The Parish Morphology

TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY

The project area covers a sample of the six distinct geomorphological zones, which can be identified at the interface of the two geographical regions (Figure 3).

Zone 1, the largest single zone, comprises the chalk downland of the Wolds top, defined to the north by the 150m contour and elsewhere by dry valleys containing extensive alluvial sands and gravels frequently capped by colluvium (Zone 1A).

Zone 2 incorporates the north facing scarp of the Wolds where the steep incline has restricted the formation of good soils, but where steep sided chalk knolls have provided an ideal setting for early settlement as in the case of the late Bronze/early Iron Age palisaded enclosures of Staple Howe and Devil's Hill (Brewster 1963; 1981).

Zone 3, spanning the basal red chalk and Speeton clay deposits between the 50m and 90m contours, incorporates the spring line and is the setting for the current settlements along the southern margins of the Vale.

Figure 3 The Geomorphology of the Project Area

Figure 4 The Parish Transect

Zone 4 was defined as a result of the recent excavations and covers the extensive aeolian sand deposits which can be traced for over 10 km both to the east and the west of the project area. The deposition of the aeolian deposits over much of the zone has served to conceal and preserve areas of relict landscapes.

Zone 5, the dry vale, covers an area of postglacial sands and gravels bounded to the south by the overlying aeolian deposits and running into the lacustrine clays of the wet vale to the north.

Zone 6, at the base of the Vale bordering the River Derwent, comprises a large flat area of lacustrine clays frequently cut by relict, and now peat filled, water courses and including a number of slightly elevated gravel islands. Although Zone 6 would have supported a fenland environment during the later prehistoric period, successive drainage schemes have dried out the greater part of the area which, as in the other zones except Zone 3, now support intensive arable farming.

PAST WORK IN HESLERTON

Work in the parish began with Greenwell's identification of a long barrow at Heslerton Wold in 1868 which produced evidence of a Yorkshire Cremation long barrow (Greenwell 1877, 142-45) This may be a separate long barrow to that excavated in 1962 by F. and L. Vatcher which still survives as an earthwork (1965) and which was also typical of the Yorkshire series of cremation long barrows. Greenwell also examined three round barrows in the parish; Barrow VI produced a number of features typical of the Yorkshire cremation long barrow tradition, a facade bedding-trench and a ritual pit, and a quantity of Neolithic pottery. Barrows IV and V illustrated the high degree of organic preservation in the area, in the former a quantity of seeds was recovered and in the latter what was thought to be preserved leather (Greenwell 1877, 142). A prehistoric burial was recorded within the former quarry works in West Heslerton in 1968 by Brewster (pers. comm.) which was accompanied by a jet necklace normally associated with Food Vessels.

Work began on a palisaded settlement at Devil's Hill in 1966 (Brewster 1981) and was completed during 1981, when a number of structures, and the enclosing palisade with its entrances, were examined in detail (Brewster, forthcoming). The relationship of Devil's Hill in Zone 2, to the contemporary occupation examined in this paper is of great importance. In addition to these excavations, Brewster undertook a programme of field-walking within the parish in the 1950s which resulted in the recovery of finds including several polished axes, prehistoric and Romano-British pottery scatters, a number of Anglian beads and medieval pottery, together with structural traces (Brewster, pers. comm.).

THE EXCAVATIONS

LOCATION OF THE SITES

Figure 5 The Project Area Map

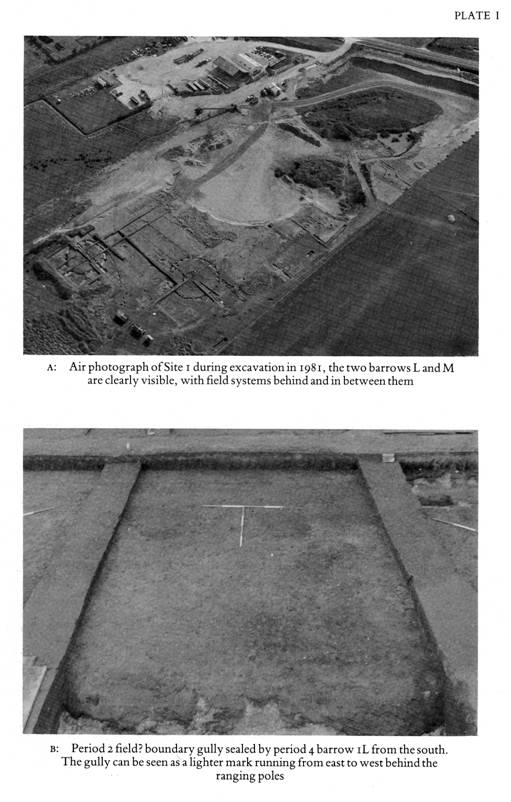

Sites 1 and 2 are located at the centre of the Parish Transect (PL. IA) extending across the whole of Zones 3 and 4 (Figure 4). Although the ground rises over 10 m towards the southern edge of Site 2 (NGR SE 91657625) the natural surface over Site 1 (NGR SE 91757670) dips away to the north at a uniform gradient, dropping only 5 m over 700 m and would have provided an ideal setting for early occupation with light, easily worked sandy soils. Access to the chalk uplands and the wetlands at the centre of the Vale would have been easy at most times and provided a wide range of ecological zones. The principal line of communication would have been to the east and west, along the Vale margin, providing access to the coast with its important flint deposits and to the Vale of York. To the north, routes would have been restricted, while to the south a number of dry valleys provide easy access to the Wolds, the plain of Holderness and the Humber. Excavation and air photography have indicated the presence of a series of relict stream channels draining into the vale from the spring line at the foot of the Wolds. These water courses, which appear to be regularly spaced at c. 200 m intervals, must have provided an important source of water, reducing the need for wells and the resulting requirement for nucleated settlements.

Figure 6a Location of Sites

Figure 6b Site Plan showing Area codes

SOILS By Richard MacPhail (M1/76-97, M2/ 1-10)

The surface geology over both sites comprises sands and gravels derived as postglacial outwash from Forge Valley in the north-west corner of the Vale. From the southern edge of Site 2 chalk gravels give way to the mixed sand and gravel deposits characteristic of Site 1. The horizontally bedded sands at the southern edge of Site 1 are interspaced with chalk gravel which increases in density until at the northern limit of the site the quantity of sand is minimal. A complex sequence of erosion and deposition, starting at least as early as the late Neolithic, had left large parts of Site 1 capped with deposits of aeolian sands which in the central area (1D, 1K, 1L, 1M, 1N, 1P, and parts of 1R, 1S, 1T, and 1X) had preserved early ground surfaces from subsequent erosion and plough damage. Elsewhere on Site 1 plough damage had truncated the archaeological deposits to varying degrees in areas 1A and 1B in the south, and areas 1R, 1S, 1T, and 1X in the north.

METHODOLOGY (M1/72-74)

THE RESULTS

PERIOD 0: THE EARLIER MESOLITHIC (M1/75)

A series of relict stream channels emerges from the spring-line at the foot of the Wolds and is important both for site topography and water supply. Detailed examination of two of these provided evidence of erosion and depositional processes from the early Boreal phase onwards (Zylawyj, M2/11-17;M3/02)

PERIOD 1: THE LATER MESOLITHIC

THE EVIDENCE

No archaeological features can be assigned to this period, human activity being indicated solely by the lithic assemblage. This evidence is discussed in detail in two reports by Gillian Wilson presented originally on microfiche (M1/01-71), now linked as Flint Reports 1 and 2, from which the evidence below has been abstracted.

Three phases of flintworking can be isolated, all demonstrable through cores, tools, and debitage, the distribution being illustrated in Figure 7. The earliest, represented by microlithic tools, micro-cores and a number of blanks, represents about ten per cent of the total assemblage from Site 1. Given that the greater part of the assemblage is debitage rather than readily dateable tools the two criteria of breadth (< 10 mm), and method of detachment (indirect percussion), have been used to isolate what may be considered a minimum count of primary phase or late Mesolithic blanks.

The relative frequency of material attributable to this period is indicated in Table 2. Although the frequency of Mesolithic material remains fairly uniform when expressed purely as percentages of the total assemblage per excavated area, the density varies dramatically from one part of the site to another, ranging from 1 per 5.3 sq.m in area 1A to 1 per 4050 sq.m in areas 1T and 1X. The high densities present in areas 1A, 1B, 1E, and 1F towards the southern end of the site are of considerable importance. In these areas the density variation may to some extent be due to differential rates of recovery, but this alone cannot explain the differences.

The assemblages from areas 1B and 1F included cores, debitage, and identifiable microliths; those from 1A and 1C included a considerable quantity of debitage accompanied by microliths. In area 1B, where the proportion of tools and cores was the highest, a much higher density can be postulated since although the area investigated was quite large, c. 750 sq. m, only a small portion had not already been truncated by stripping. All the microlithic pieces were recovered from a strip covering a 15 by 15 m area against the western limit of excavation, where the sealing layers of blown sands appeared to be increasing in depth, producing a density of 1 per 5.7 sq. m, a figure which closely matches the high density in area 1A.

DISCUSSION

Besides a number of tools (including rods, crescents, edge-blunted points, backed blades, and an awl) and cores the material attributed to this period includes a large amount of debitage (278 pieces) which is viewed as a minimum rather than a maximum count. Thus it is clear that flint was worked on site during this period and that this activity was concentrated at the southern and western margins of the site in areas 1A, 1B, 1E, and 1F, the highest concentrations indicating a relationship between the flint knapping areas and the relict stream channel. It is unfortunate that the area between the high concentrations located in areas 1A and 1E was quarried away prior to the start of the excavation. Although the natural sands and chalk gravels of the site contain a large quantity of chert it is of very poor quality and all the raw materials of the lithic industries at both sites were imported.

Figure 7 Plan of Periods 0-3 (Earlier Mesolithic, Later Mesolithic, Middle Neolithic and Later Neolithic)

PERIOD 2: MIDDLE-LATE NEOLITHIC

THE EVIDENCE (PL. IB)

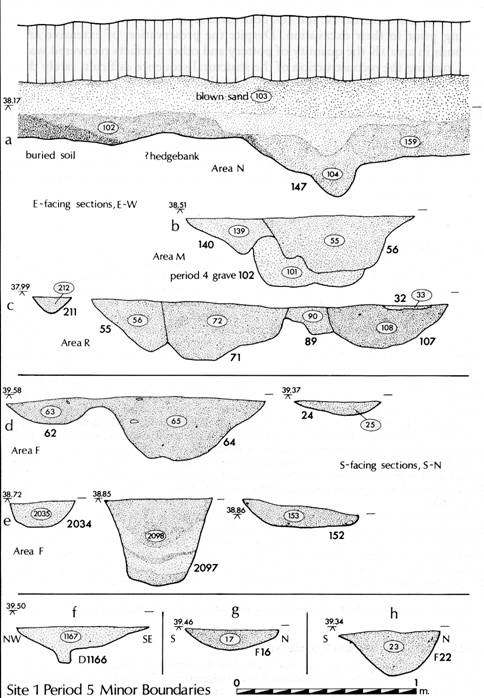

The earliest man-made features are a series of ten ditches aligned broadly east-west. None produced artefacts but stratigraphic precedence was established to phase 3A pits, phase 4 burials and the mounds of barrows 1L and 1M. They are consistently of U-profile and less than 0.5 m deep. In two cases, in areas 1X and 1N, the ditches are paired, perhaps as quarries for hedge banks. Thin-section analysis of the fills (MacPhail M2/01-10) suggests that the ditches had been cut through a brown earth indicative of agricultural activity.

Figure 8 Period 2 ditch profiles

DISCUSSION

The total lack of artefacts from any of the segments examined reduces the degree to which these features may be interpreted; however the uniformity of profiles, scale, fills, and alignment suggests that the whole group is both contemporaneous and part of a system of land division or fields. If they are to be interpreted as early field boundaries then the lack of any elements running north-south must be explained. Given the presence of the active stream course on the western margin of the examined area and a second, still active, to the east an acceptable system may be reconstructed in which the stream channels form the principal north-south boundaries. This arrangement would provide a series of 'fields' covering a 30m by 200m area at maximum.

PERIOD 3: THE LATE NEOLITHIC

THE EVIDENCE

Three groups of Pits (3A-3C) are attributed to this phase by morphology or assigned function. They share a distinctive very dark fill (Munsell 10/YR/21-32), otherwise matched only in buried soil horizons and Period 4 barrow mounds and graves.

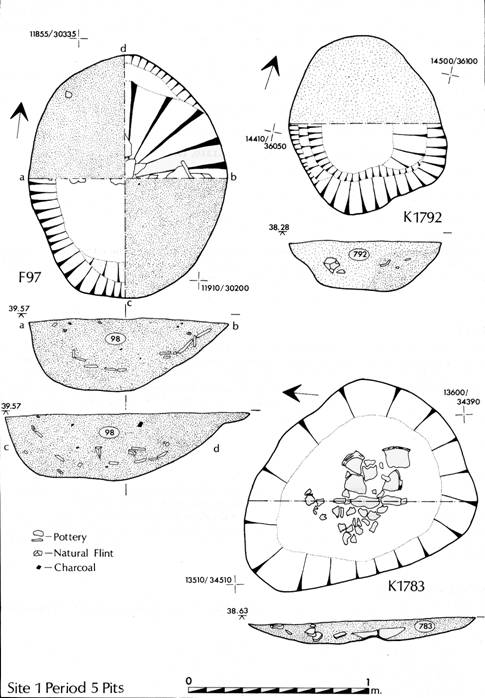

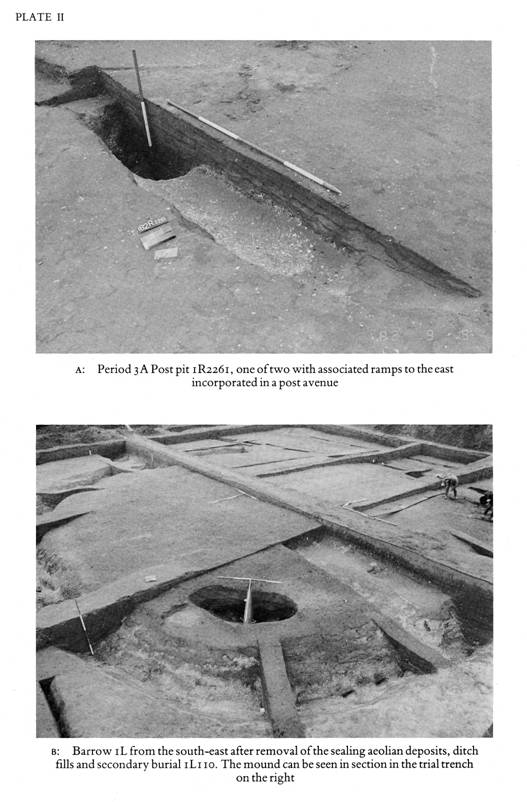

GROUP 3A (Figure 9, PL. IIA)

Figure 9 Period 3A pits: Sections and Plans

Eight large pits have been identified. All apparently had held massive posts and they appeared to form two irregular but parallel north-south alignments traced over some 175 m. The largest example (1R256) was sealed by Barrow 1R and was 1.6 m in diameter, 1.6 m deep with a ramp from the NE 2m long; a post diameter of c.0.6 m could be inferred. Its neighbour (1R261) was of comparable size and again ramped with a clear post-pipe c. 0.4 m in diameter. The remaining pits were smaller but could still have held substantial posts.

GROUP 3B

This comprises over 40 widely-dispersed pits, grouped by fill and morphology. Most were ovate with near-vertical sides, a sloping base, and a uniform infill. Two were sealed by a Period 4 barrow mound (1M235, 1M237) and another cut by a barrow ditch (1L1153); several preceded Period 5 features (1E1519, 1C2426, 1K1859).

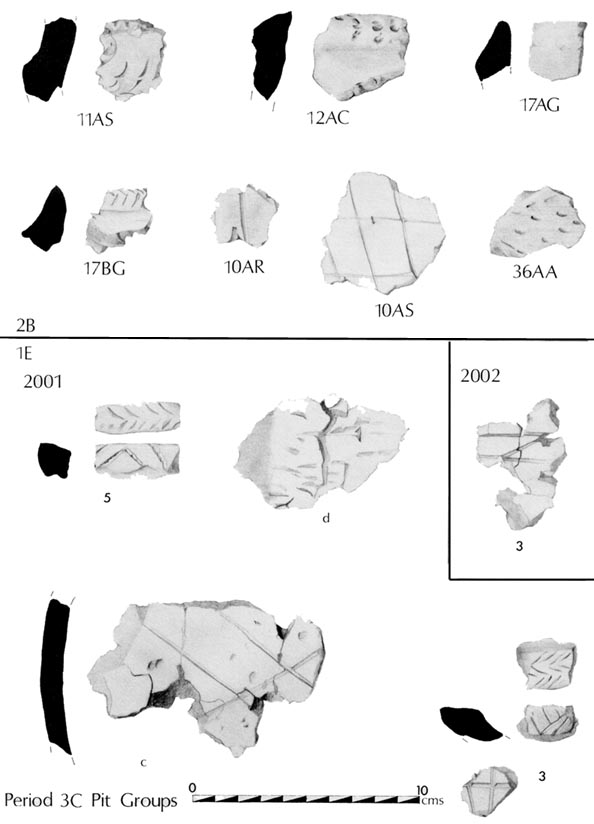

GROUP 3C (Figure 10)

Figure 10 Period 3C Pit Pairs

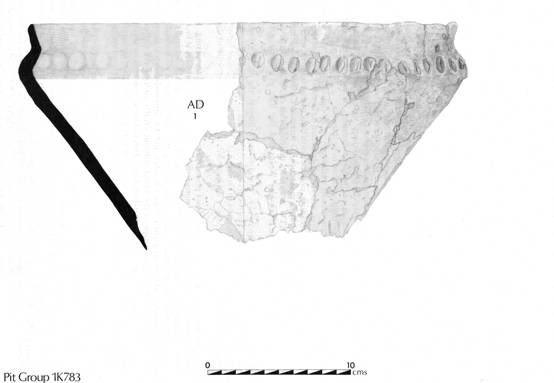

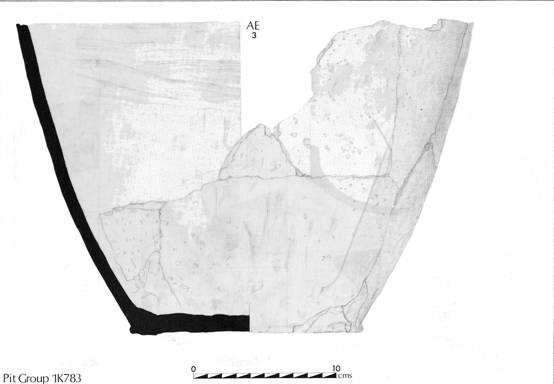

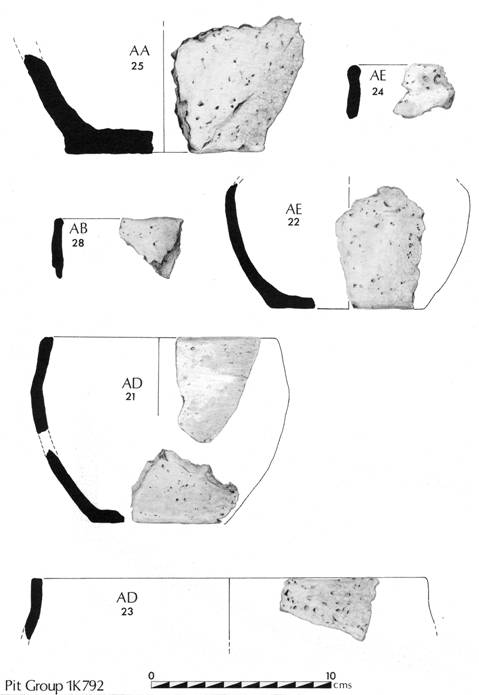

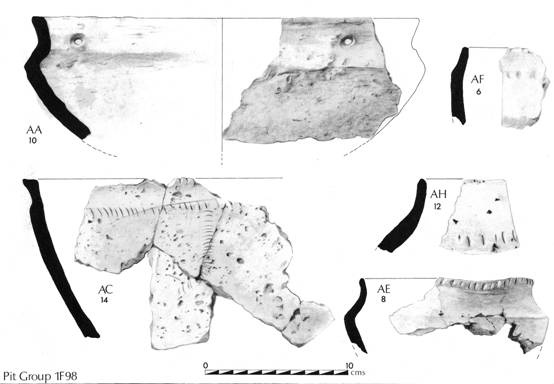

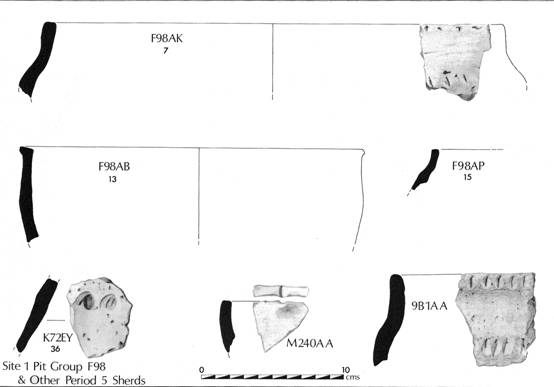

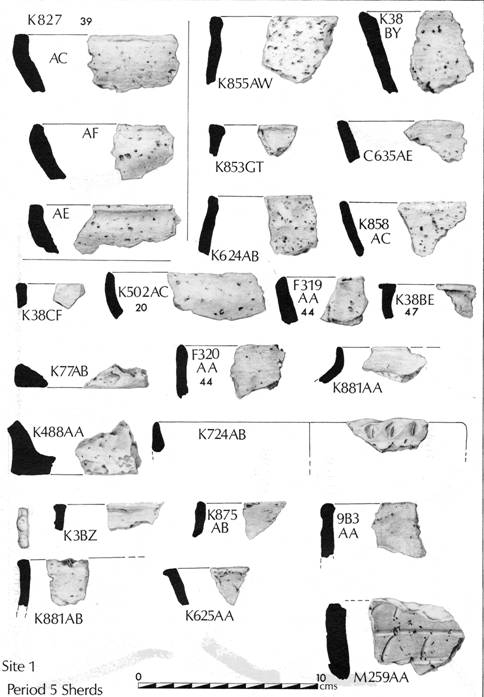

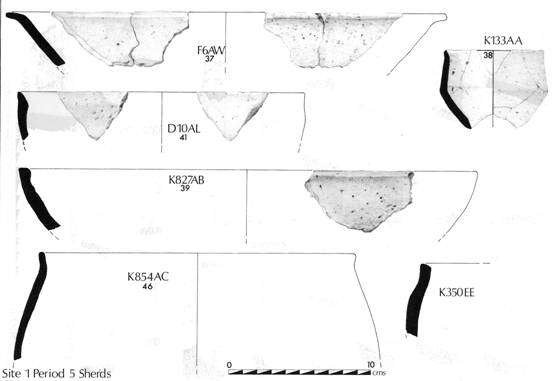

Two pairs of pits produced quantities of later Neolithic pottery and other material. The first (1E2001 and 2002) were excavated by J. Dent in 1977-78 and lay 2m apart. Both were circular, 0.8 m in diameter, and flat-based, depths 0.34m and 0.11m with fills of dark sand. Contemporaneity can be presumed from the pottery represented (Figures 11 and 12). The second pair (2B16 and 20) were m and 0. 0.97 m in diameter and 0.4 m deep with a black sandy fill incorporating carbonized material including burnt bone and hazelnut shells. The pottery (Figures 12 and 13) and a fragment of jet cylinder bead were concentrated in the upper fills.

OTHER EVIDENCE

Apart from scattered material, especially in the southern part of Site 1 and beside the relict stream channel in areas 1E and 1F, features likely to be of this period were sealed by Barrows 1M and 1R. Beneath the south-west side of 1M was a row of six post-holes aligned NE-SW, and at the east side was another group defining a possible ovate structure, 5 m by 3.5 m in area. A much-damaged scatter of post-holes lay beneath the north side of 1R.

The total flint assemblage, including scattered material, comprises over 4000 pieces and ranges from imported raw materials to finished products, representing earlier Neolithic to early Bronze Age traditions.

D1SCUSSION

Three basic phases in the 1ithic material have been identified, one of which, the Mesolithic, has been assigned to period 1 (seeM1/25, M1/66). The remainder, about 90 per cent of the overall assemblage, dates from the Neolithic and early Bronze Age. The presence of serrated blades, leaf-shaped arrowheads, and a single laurel leaf indicate earlier Neolithic activity, particularly in area 1F, a suggestion which gains some support from the examination of the debitage. Following the scheme suggested by Pitts and others (M1/32) in which the blade industries are assigned to early, and broad flake industries to late Neolithic phases, Wilson has demonstrated a marked concentration of blades in areas 1F and 1B. The lack of any early Neolithic material in the ceramic assemblage however indicates that at this period the foci of activity must lie elsewhere; the small number of tools, and in particular the arrowheads, could result from casual loss. Although this distinction between the early blade and later flake industries may be tenable with reference to material in Wessex, there is no reason to believe that this distinction should be so readily accepted in the North. During the late Neolithic concentrations of ceramic material, particularly Peterborough type wares, both within the Period 3C pits and elsewhere indicate some degree of domestic activity. Apart from the pit groups the highest densities of late Neolithic material were in areas 1F (39 sherds) and 1A (17 sherds), and even though this suggests some degree of activity it must still have been limited, the distributions perhaps being peripheral to more extensive activity to the south and west of Site 1.

Regardless of whether this distinction between early and late Neolithic lithic material can be accepted in the light of the limited ceramic assemblage, which is predominantly later Neolithic, that the site was a centre for flint knapping can be readily accepted. The flint assemblage, amounting to more than 4000 pieces, includes the complete spectrum of material from imported raw materials through to finished products. This flint knapping industry, concentrated in the same areas as that related to period 1 cannot be closely related to the feature groups discussed above.

The phase 3A pits are the most distinctive of the pit groups and appear to be post pits which may be interpreted as the component parts of an irregular avenue crossing the site from the south-south-west in a north-north-easterly direction, comprising two alignments, 3AA and 3AB (Figure 7). Three of the pits certainly contained massive posts and there is no reason to believe that the other pits in the series did not perform the same function. The limits of the site preclude more detailed interpretation at present. but it is possible that further evidence may come to light in future extensions of the quarry, particularly to the west, which would allow for a more detailed assessment.

The phase 3B pits are perhaps the most difficult to interpret; they were readily definable during excavation as a coherent group, based upon morphological grounds, and it is assumed that this must relate to their function. The well-defined and frequently vertical sides indicate that they must be man made but their function must remain unknown.

Figure 11 Pottery (Period 3C) from Area 1E

The phase 3C pits belong to a class widely recognized both in eastern Yorkshire (Manby 1974) and from elsewhere (Bradley 1982). The pairing of these pits is an important feature which has been identified at a number of the Grooved Ware sites on the Wolds collated by Manby (1974). Both contained extensive assemblages which cross-relate in each pair, indicating contemporaneity of the backfilling. In both cases the material would seem to derive from a domestic context and its concentration in the upper fills suggests that it was deposited there as a secondary function of the pits.

Figure 12 Pottery (Period 3C) from Areas 1E/2B

Figure 13 Pottery (Period 3C) from Area 2B

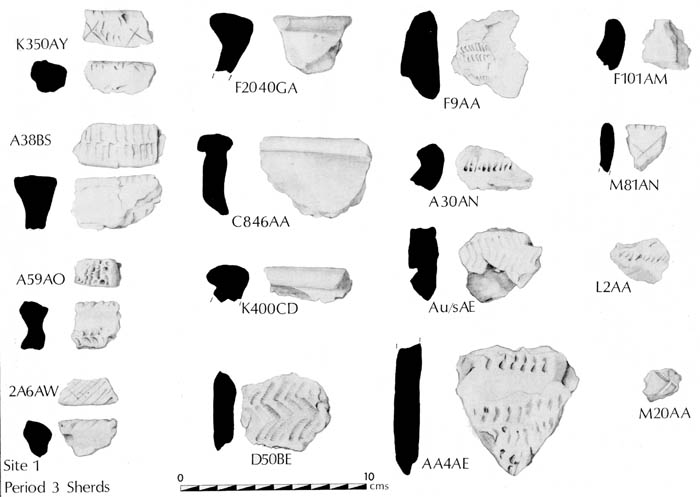

Figure 14 Other Period 3 pottery

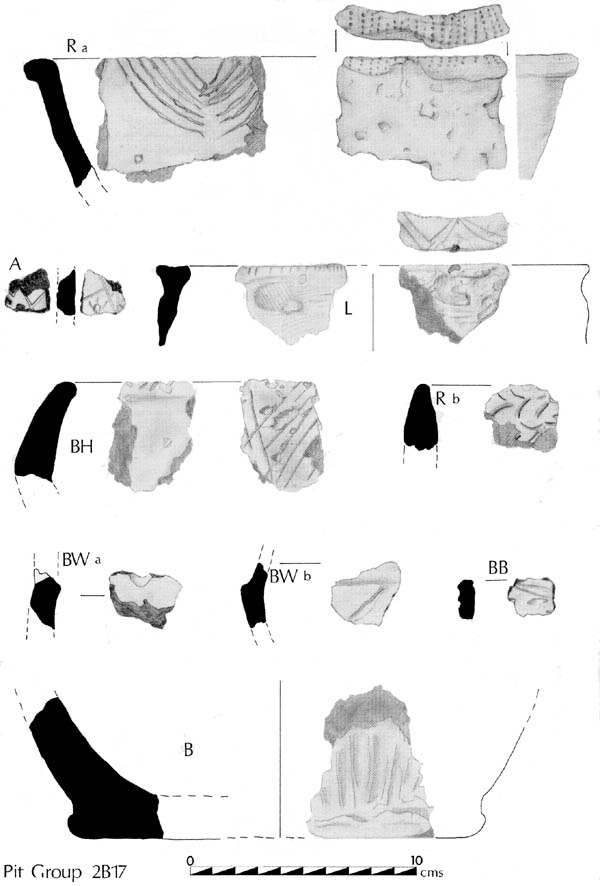

THE LATE NEOLITHIC POTTERY by T. G. Manby (M2/23-43)

Towthorpe Style

Three pieces appear to be from vessels of the Middle Neolithic Towthorpe style: 1C846 AA, 1K400 CD, 2B U/S. The first two may be pieces of the same vessel.

Peterborough Ware

The main spread of sherds at Heslerton Site 1 consists of Peterborough Ware with some Beaker sherds of small size. The principal assemblages comprise the sherd groups from two pits, 1E2001 and 2002. There are no complete vessels, but at least three, probably six vessels, are determinable from pit 1E2001 and five vessels from pit 1E2002. The fragments show little evidence of weathering, the broken edges are uneroded. The general characteristics allow attribution to the Fengate style and the prevailing vessel form can be reconstructed as tall jars with deep collared rims, the body running downwards at a steep angle to a narrow flattish base. Decoration shows a preference for fingernail impressions to form herringbone patterns on the internal rim bevels. The same technique applied to the collars produced standing and pendant arc patterns. Arcs were also produced in cord maggot, used for lines on rims and collars. A sharp point was employed on some vessels to produce the herringbone on the internal bevel; it was used for the criss-cross lattice on the bodies. Some vessels display pits on the bodies immediately below the collar. A further technique observed is finger-tip rustication to furrow the collar.

All these decorative methods and motifs can be paralleled at the Fengate type site (Leeds 1922, B10-12, 15, 17 & 21) at Peterborough. Further Fengate style collared vessels come from Salmonby, Lincolnshire (unpublished; Lincoln Museum), Mount Pleasant, Derbyshire (Garton and Beswick 1983, 19-20) and the East Yorkshire sites of Driffield and Acklam Barrow 211 (Manby 1957a). Closely related in shapes and decoration to West Heslerton are the conical vessels from Thirlings, northern Northumberland, where one pit produced a carbon 14 date of (HAR1451) 2130 + 130 bc (Miket 1976, 119, Figure 7. 10-12). The few C14 dates associated with Fengate style pottery has been noted to extend over half a millennium and pre-dating (BM-75) 1540 + 156 bc at Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure (Garton and Beswick 1983, 20).

Extending the collared profiles and the preferred fingernail-incised motifs of Fengate-Heslerton assemblages are the wider range of vessel forms and decorative motifs provided at the Wold site of Carnaby Top Site 19 (Manby 1975, 41-44, Figures 13-14). Here are elaborately moulded hammershaped rims with internal ridges, and there is a preference for incised herringbone patterns. T-rimmed vessels with incised decoration are present amongst the Fengate style assemblages at Driffield (Manby 1957, Figure 2.5), and Fengate (Leeds 1922, Figures 11 and 12). The weak neck and rounded shoulder of these vessels bear little resemblance to the well-modelled forms at Carnaby Top and their decoration is of a simple casual character. This element is also present at Heslerton.

The Late Neolithic date for the Fengate style is emphasized by the occurrence of scattered Beaker sherds. The development of this style of Peterborough Ware over its very wide geographical distribution, from Kent to Wiltshire and northwards to Northumberland, is not at present fully understood. It emerged as one of the Peterborough styles of Burgess's Mount Pleasant Period c. 2750 B. c. to 2000 B. C. which was also the period spanned by Steps 1 to 4 of Lanting and van der Waals British Beaker sequence (Burgess 1980, 37-68). It is likely that a Fengate assemblage with a wide range of vessel forms including hammer-shaped rims such as Carnaby Top Site 19 is earlier than the Heslerton assemblage. The Carnaby Top material has a great proportion of elements derived from earlier Ebbsfleet, Mortlake, and earliest Rudston styles (Manby 1975, 54-5 5). The development of the Peterborough styles, Mortlake, Rudston, and Fengate, is not a linear series, but overlapping and parallel developments chronologically and regionally, that culminated in the Food Vessel and Collared Urn traditions of the early Bronze Age.

The Carbon 14 Dates

A number of radiocarbon dates are awaited relating to the complete activity sequence at the site. Discussion of these dates will appear in a later report. Those dates which are available are referred to under the relevant sections of the text.

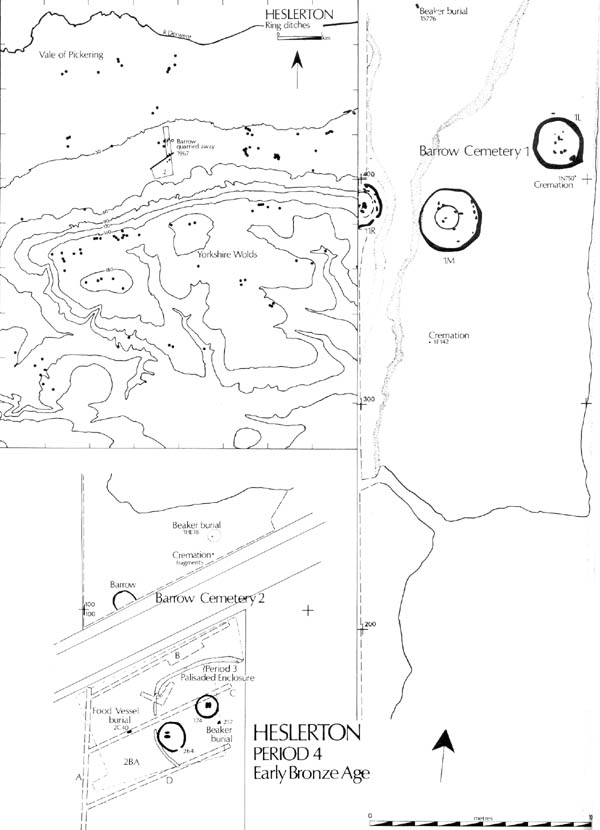

PERIOD 4: THE EARLY BRONZE AGE

THE EVIDENCE

Period 4 represents one of the three principal phases of activity at the site and is represented primarily by two round barrow cemeteries. Barrow Cemetery 1 was located at the centre of Site 1 in areas 1L, 1M, and 1R, while Barrow Cemetery 2 was situated 300 m to the south in areas 1A and 1HE, extending beyond the limits of Site 1 onto Site 2 to the south. The full limits of neither cemetery were examined; in the case of Barrow cemetery 1 the presence of a barrow to the east of Site 1 may be inferred from the discovery of a burial accompanied by a jet necklace of Food Vessel type during quarry operations in 1967, while further barrows associated with this cemetery are indicated by crop marks to survive in the adjacent field (Site 10). Further barrows associated with Barrow cemetery 2, which survived to a lesser extent on account of plough damage, may be inferred on Site 2 by the excavation of the Food-Vessel burial 2C40. The level of structural preservation was outstanding in the case of Barrow Cemetery 1 however, particularly in the case of Barrow 1L.

Figure 15 Eastern Yorkshire : Location of Barrows

BARROW CEMETERY 1

If the burial accompanied by a jet necklace and located during quarrying in 1967 was indeed interred in a barrow, as is suspected, this (see Figure 15 for location) cemetery comprised at least five barrows. Two, 1L and 1M, were entirely within the threatened area. A third 1R, extended beyond the threatened area and thus only half was excavated. The fourth lay to the east while the fifth is indicated as a crop mark in the adjacent field to the West (Site 10). Three flat burials and two cremations located beyond the limits of any barrow demonstrate that burial practice was not restricted to ground enclosed by the barrow ditches. The evidence for each of the three barrows examined is discussed individually below.

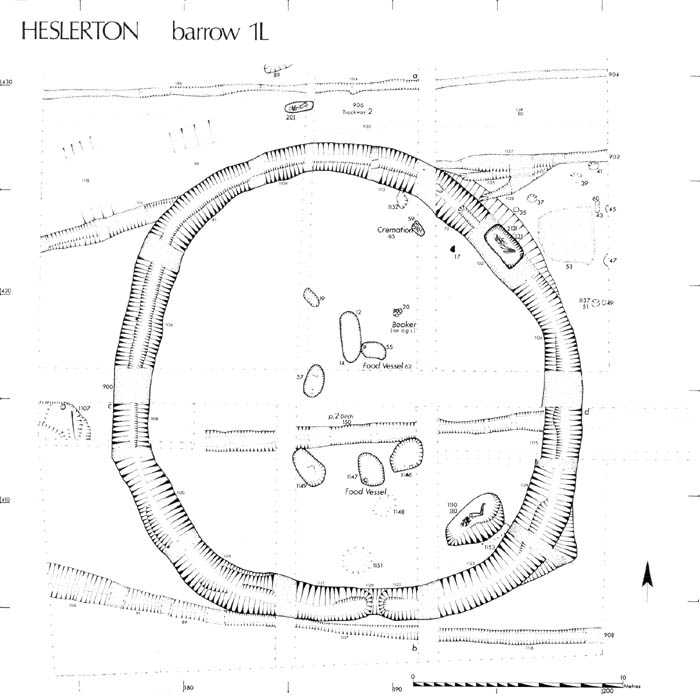

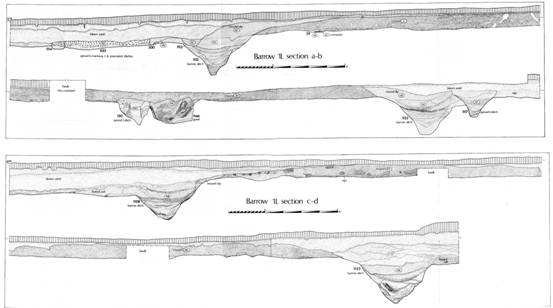

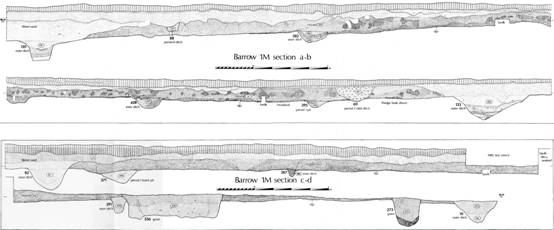

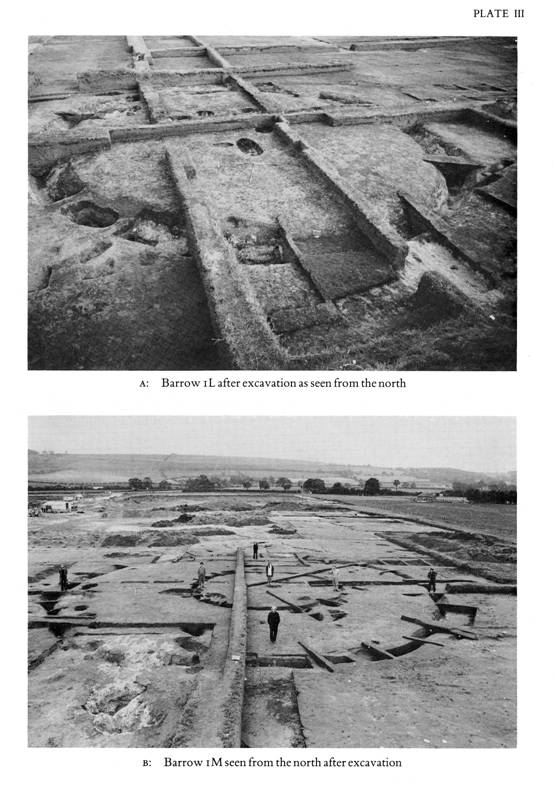

Barrow 1L (Figure 16, Pls. IIB, IIIA)

This, the best preserved of the barrows, was entirely sealed by a capping layer of blown sand; thus the mound survived intact cut only by three graves and by a small number of very shallow plough marks, although the ditch had in places been cut by period 6 ditches. The monument was defined by a 1.5-2.5m wide, sub-circular ditch flattened on the southern side, measuring 22m in diameter and enclosing an area of c. 380 sq.m. The mound, which survived to a height of c. 3m, had partially slumped across the filled ditch.

Figure 16 Barrow 1L Plan

The Mound (Section: Figure 74)

The mound, which was almost flat on the top, with a slight depression on the southern side, was composed of a homogeneous dark brown/black sand (Munsell range 10/YR/21 to 10/YR/32) which was virtually stone-free.

The examination of the deposits at the base of the blown sand around the perimeter of the barrow indicated that at the time the old land surface was scaled a turf deposit was not present. Dr MacPhail, in his report on the soils (M2/08), has suggested that the Period 2 ditch 1l150, sealed by the barrow mound, had been part of an agricultural landscape and that much of the barrow mound material must derive from A-horizon material. The lack of stone in the mound matrix may imply that the soil was derived from an abandoned agricultural and heavily worm turned soil, in which case part at least of the mound matrix may derive from the ground surface around the perimeter of the barrow. An increase in the density of stone at the base of the mound was identified with the interface of the mound and the old ground surface, and it may be that this concentration resulted from worm action in the mound redistributing the stone element that had been derived from the cutting of the ditch. Dr MacPhail has argued that prior to the construction of the mound the old ground surface was already denuded, perhaps through wind erosion, as one might expect after the abandonment of agricultural activity.

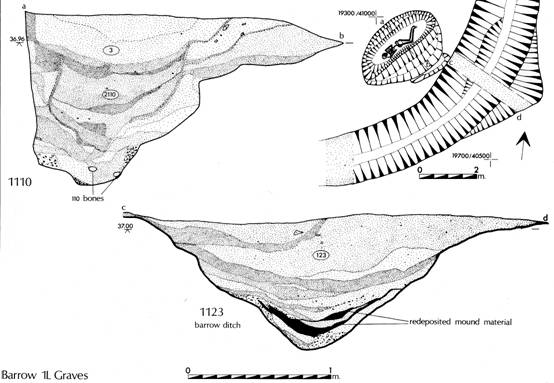

The Ditch

The barrow ditch had a regular broad V-shaped profile which was uniform except on the southern side, where there may initially have been a causeway. The depth ranged between 0.8m and 0.2m. Apart from limited cleaning in association with the backfilling of grave 1L1110, the ditch had not been cleaned or recut. The fills could generally be broken down into three layers: a primary silt composed of mixed sandy-silt and gravels; secondary silting comprising a mixed silty-sand combined with aeolian sands; and finally a stabilization layer of aeolian sand combined with loamy sand and barrow mound material. The fills in segment 1L1123 followed the same basic pattern as elsewhere except in the lower 0.3m, where redeposited mound material combined with evidence of cleaning give a different picture. The ditch profile had been widened on the outer edge by a shallow scoop which, on excavation, gave the impression of a squared-off corner to the ditch. This change in profile and the more complex sequence of ditch fillings may be attributed to a cleaning up operation associated with the insertion of the burial in grave 1L1110 0.5m to the north-west. This burial must have been inserted soon after the barrow mound was thrown up, certainly within six months; part at least of the soil derived from digging the grave pit had been thrown out across the ditch to the south-cast such that when the grave was backfilled, cleaning against the outer edge of the ditch broadened the profile which extended 0.65 m into a shallow scoop beyond the edge of the ditch proper.

The Burials

Nine burials were located within the area covered by the barrow; a further three were discovered in the immediate vicinity. Two examples were cremations, the remainder inhumations, two being accompanied by Food Vessels. The well-preserved nature of the barrow mound meant that it was possible to isolate the relative sequence of the burials with a high degree of certainty. The level of bone preservation in the majority of the Period 4 burials was very low, only surviving to any great extent where burials had penetrated the chalk gravel layers in the natural.

Primary Burials

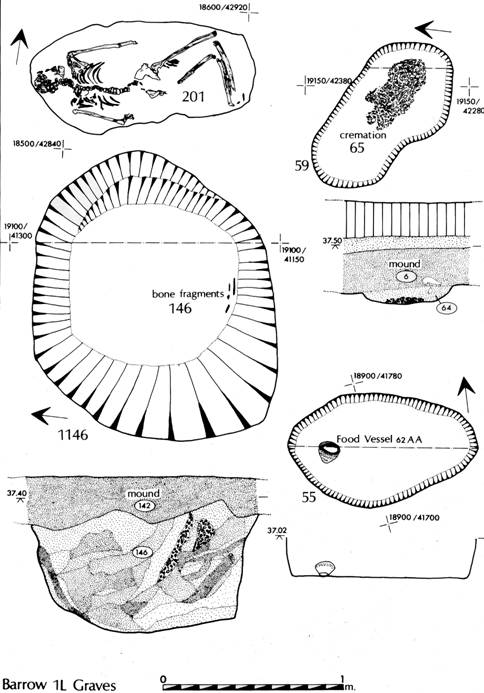

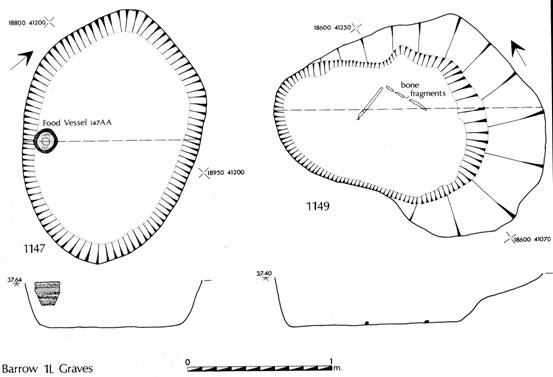

Five graves were isolated in a primary position: four inhumations, 1L1146, 1L1147, 1L1149, and 1L55 lay within the central area, whilst the fifth, a cremation, 1L59, was located near the northern perimeter of the monument.

1L1146 (Figure 17), which cut the Period 2 ditch 1L150, was an ovate cut with vertical sides and a flat base. The generally homogeneous sandy matrix filling the grave included a patch of redeposited natural chalk gravel against the southern side, which led to the preservation of sonic fragments of adult long bones, probably male.

Figure 17. Barrow 1L: Primary Burials.

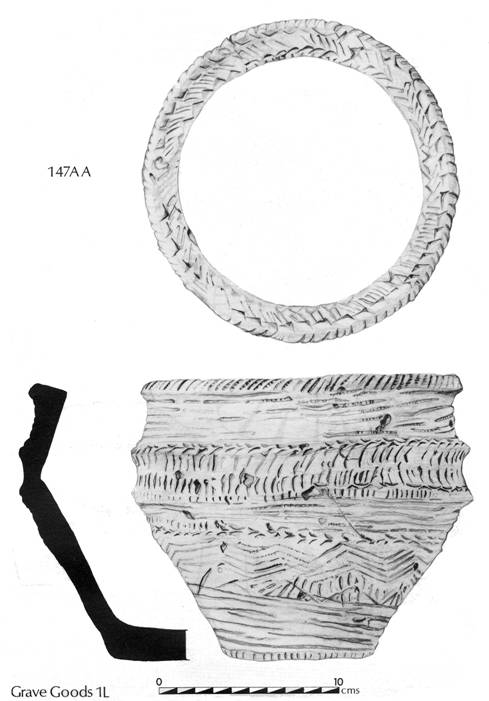

1L1147 (Figure 20), a sub-rectangular and shallow cut, contained no surviving bone traces but did contain an upright Food Vessel (1L147 AA, Figure 18) located against the south-west corner of the cut.

1L1149 (Figure 20) again cut the Period 2 ditch 1L150 and was sealed by the mound. It contained no artefacts but did contain fragments of long bones and staining indicating a crouched or flexed burial of indeterminate age and sex lying on the left side with the head to the north-west.

1LS5 (Figure 17) was the smallest of the grave cuts and, in the absence of any surviving bone or staining, was presumed to have contained an inhumation of a child. That the feature had been a grave was indicated by the presence of a small Food Vessel (1LS6AA,Figure 19) lying on its side at the western end of the cut.

1L59 (Figure 17) appeared to be the latest of the primary graves and contained the cremated remains of a young adult 1L65, which lay in a shallow scoop in the old ground surface. The mass of clean cremated bone was very well defined and appeared to have been contained. One metre to the west of the cremation an extensive deposit of charcoal, 1L17, lay on the old ground surface. This deposit, derived from some sizeable timbers, may be related to the cremation. The C14 date of this material provides a terminus post quem for the construction of the mound: (HAR-6690) 3840 + 40 b. p. (1890 bc).

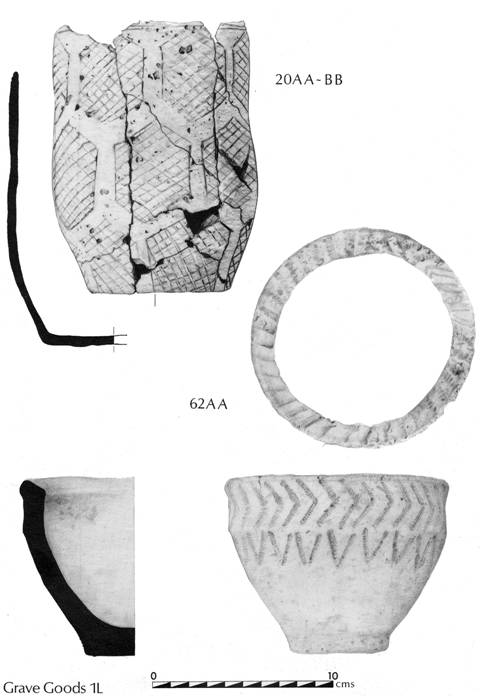

Most of an S4 Beaker, 1L20 AA (Figure 19), was also found in a primary position, lying on the old ground surface beneath the northern side of the mound. The vessel had been smashed in antiquity and did not appear to relate to any burial.

Figure 18. Barrow

1L: Pots (Food Vessel).

Figure 19.

Barrow 1L: Pots (Food Vessel and Beaker).

Figure 20.

Barrow 1L: Grave Plans (1147, 1149).

Secondary Burials

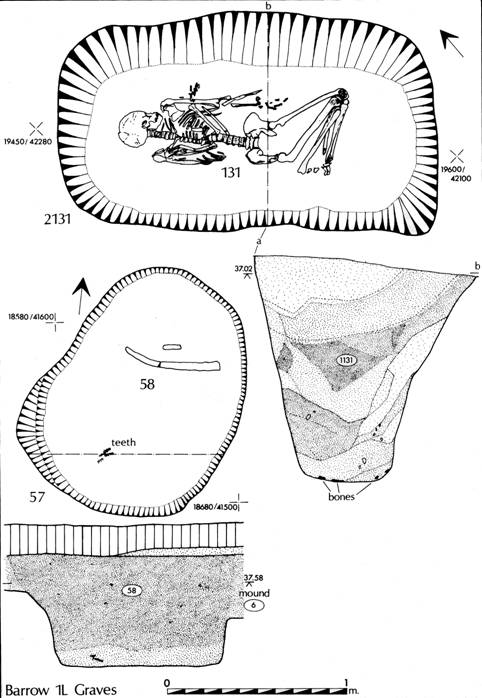

1L57 (Figure 21) was located nearest to the centre of the monument and may possibly have been a primary cut. The mound matrix and the grave fill were practically indistinguishable and although this feature could not be distinguished in plan on the mound surface, there was a slight indication in section of an associated cut through the mound. The grave contained no artefacts but did contain the poorly preserved long bones and tooth-caps of a young adult of indeterminate sex in a crouched position on the right side, facing cast with the head to the south.

Figure 21. Barrow 1L: Grave Plans (57, 2131).

1L12 (M3/01) The secondary nature of this cut was much more obvious than in 1L57 above on account of the presence of quantities of aeolian material in its upper fill. The mixing of aeolian sand with the fill may indicate that it post-dated the construction of the mound by a considerable time; it contained no artefacts and only the slightest suggestion of a body stain, which could not be adequately defined.

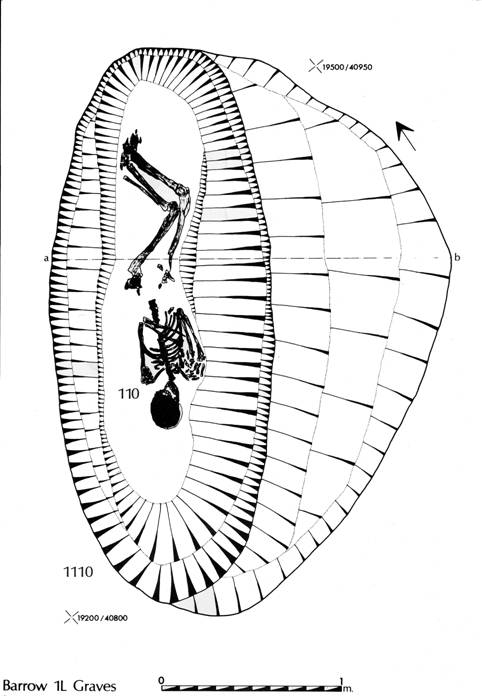

1L1110 (Figs. 22 and 23), the most important of the secondary cuts, was located adjacent to the ditch in the south-east quadrant of the barrow. Its relationship to the ditch has been discussed above. The cut was by far the largest and contained the well-preserved bones of an adult male aged between 25 and 30 years. The body, which was flexed, lay on its back with the head to the south-west with the hands possibly clasped to the right of the cranium. The burial was unaccompanied. The C14 date for this burial will provide a terminus ante quem for the construction of the mound.

Figure 22.

Barrow 1L: Grave Plan (110).

Figure 23. Barrow 1L: Grave 110 Location Plan; ditch section.

Tertiary Burials

One grave, 1L2131, may be considered to be represent a tertiary burial. Three other burials, 1L201, 1L83, and 1N750, cannot be securely linked with the phases of grave activity since they lay beyond the limits of the monument.

1L2131 (Figure 21) was a deep rectangular grave cut containing the well preserved skeleton of an adult male aged 25-30 years old, laid on the left side facing east with the head to the north-west. The legs were tightly contracted, the upper body extended and supine. This grave had been cut through the barrow ditch which by this time had almost completely filled in; the C14 date for the skeleton thus provides a terminus ante queen for the stabilization of the ditch.

1L201 (Figure 17), the prone burial of an adolescent female, lay three metres beyond the northern limit of the barrow ditch. Its relationship to the barrow had been destroyed by the Period 6 trackway which sealed it and had removed almost all evidence of the grave cut itself. The burial, which was aligned east-west with the head to the west, was unaccompanied.

1L83 was a shallow cut, at first thought to be a rubbish pit. It contained, however, a number of fragments of human bone including part of the shaft of an adult right tibia. The feature was almost certainly a grave but had been greatly disturbed by the northern boundary ditch of the Period 6 trackway which cut across the northern edge of this barrow.

Associated Burial Area

1N750, a cremation located eight metres to the south of the barrow but presumably related to it. The deposit, discovered in a baulk after completion of excavation of the area, was badly disturbed by animals; no associated artefacts were recovered. Insufficient bone was available for analysis.

The Human Bones by Jean Dawes (M2/18-19).

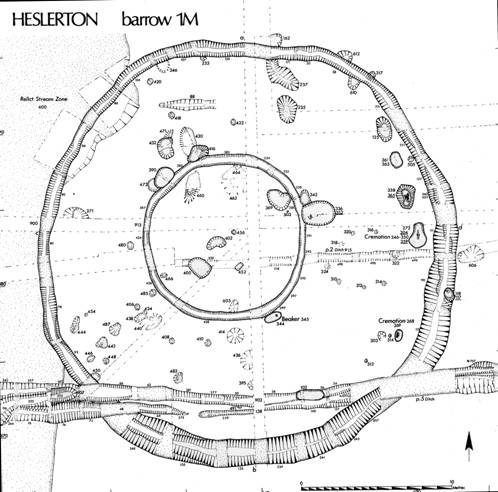

Barrow 1M (Figure 24, PL. IIIB)

This, the largest of the barrows examined, was located in the centre of the excavated area 65m to the south-west of barrow 1L; it was excavated in its entirety. Immediately to the west of this monument the relict stream channel separated it from barrow 1R 35m to the north-west. A small ring gully enclosed an area 10m in diameter at the centre of the monument, perhaps representing a primary phase; the main barrow ditch enclosed an area 25 m in diameter, its centre offset from that of the inner ring gully.

The Mound (Section: Figure75)

The mound was partially denuded, in particular on the western side where it appeared to have been eroded by stream activity. As with the other barrows in this group the mound matrix was heavily oxidized, individual turves could not be identified, and it was virtually impossible to isolate the interface between the mound and the old ground surface. The presence of a large fragment of a Food Vessel (1M3 6AA, Figure 27) on the mound surface in the centre may indicate that the mound itself had contained one burial at least, but that it had been destroyed by subsequent erosion.

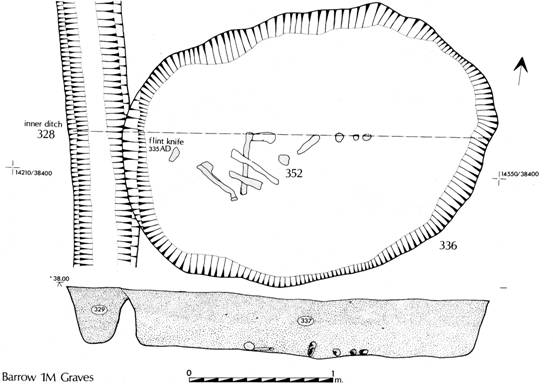

Figure 24. Barrow 1M: Plan.

If the ditches served as quarries for the mound material then the monument could never have stood to any great height, unless large quantities of mound make-up were brought in from the surrounding area. Taking the volume of the ditch at its largest point no more than 40 cubic metres of material would have been produced; this volume of soil, even allowing for the higher volume of loose as opposed to packed soil, would create a mound no more than 0.2 m in height if uniformly spread over the area enclosed by the outer ditch. On the inner edge of the outer ditch the black matrix was only c. 50mm thick, increasing in depth towards the centre of the enclosed area to a maximum of 0.2m, suggesting that the mound may have been largely confined to the central part of the monument. An examination of the mound in section (Figure 75) where it had been cut by the later ditch 1M60 revealed that at this point subsequent erosion through agricultural and other agencies had been restricted possibly by the presence of a hedge bank and an associated headland. The evidence from this section, when compared with adjacent areas, suggests that for the most part subsequent erosion and damage from agriculture was superficial.

The Ditches

The inner ring gully varied in breadth from 0.4m on the western side to 0.75m at its widest point; the sides were almost vertical and the depth nowhere greater than 0.25m. The fill, a stone free black sandy matrix, was uniform on all sides; a lack of any weathering layers indicating that the gully had not been exposed to the elements for any great time before it was filled. No rapid silts had formed in the base and the edges remained very well defined. Such a feature might well be considered to be structural, but there was no evidence to suggest that it had ever performed any such function. At a number of points the inner gully had been cut by later grave pits.

The outer ditch varied in breadth from 0.75 m on the north-western side, adjacent to the stream channel, to just under 2 m on the southern and eastern sides; the depth likewise varied from 0.5m to 0.9 m. On the western side the ditch had been rapidly filled soon after it was cut, probably as a consequence of flooding from the stream channel. On the eastern side the sections showed limited rapid setting followed by gradual filling with aeolian material as was observed in barrow 1L to the east. The ditch contained very few artefacts but was cut by a single grave, 1M118, which was inserted through the partially filled ditch on the eastern side. In contrast to barrow 1L there was no evidence of mound slip in the upper fills of the ditch.

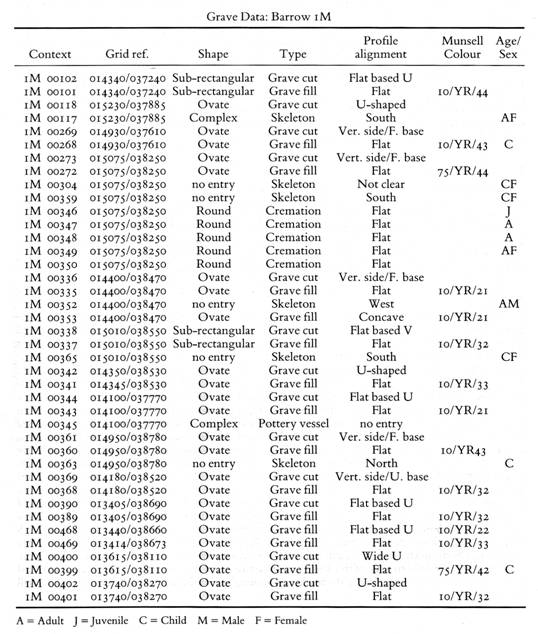

The Graves

Given the large area defined by the outer ditch the number of grave cuts was very small. The level of bone preservation was very low, few graves being deep enough to cut into the alkaline chalk gravels which occurred at a depth of about 0.5m below the surface of the natural subsoil. In a number of cases, where no bone or artefacts were recovered, there can be no certainty that features were graves and not Period 3 Pits.

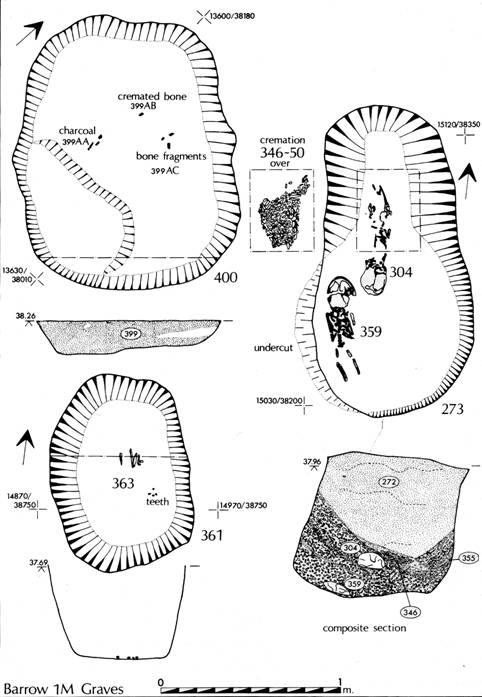

No single well-defined grave could be isolated within the central area defined by the primary ring gully; only one feature, 1M400, produced any bone, and only minute fragments. In contrast to barrow 1L the relative sequence of the grave cuts was difficult to determine, and it is assumed that the central ring gully defined the primary phase of the monument, a suggestion supported by the fact that this feature was cut by one certain and two possible graves.

Primary Burials

1M400 (Figure 25) was a shallow sub-rectangular cut, 0.18m deep and 1.32m long, which had cut through a Period 2 ditch/gully 1M915. The fill, a black sandy matrix, contained fragments of the shafts of two long bones, probably human and from a child. There were no accompanying artefacts nor sufficient bone or a body stain to indicate the position or alignment of the body. A very small quantity of burnt bone may also have been human but the quantity was insufficient to make any determination.

Figure 25. Barrow 1M: Graves 361, 400, 273

Two further cuts in the central area may also

have contained burials, 1M402, a shallow but irregular cut in the centre and

1M369 located adjacent to the ring gully on the north-eastern side. Neither

produced bone or artefacts which could be used to confirm their function as

graves. A third and much deeper cut, 1M460, was discounted as a grave on

account of its profile which compared well with the Period 3B pits.

Secondary Burials

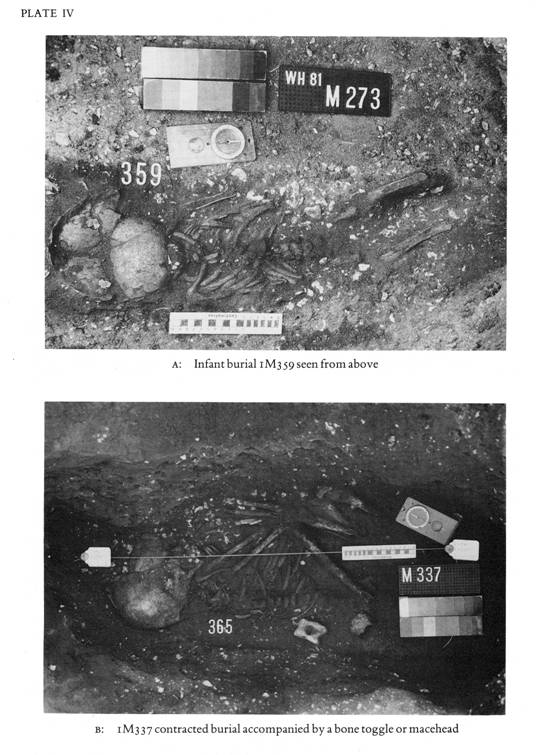

The space between the inner and outer ditches contained a number of well-defined grave cuts containing inhumations and cremations, in once case, 1M273, in the same grave.

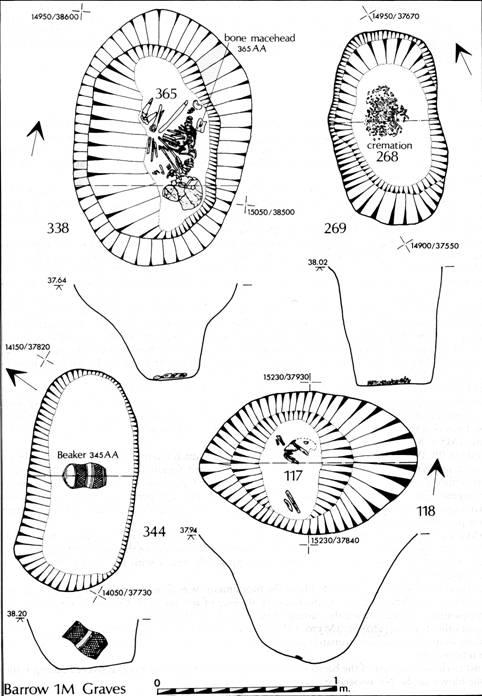

1M269 (Figure 26), a very small but deep ovate pit located in the south-east quadrant, had vertical uneroded sides and contained the cremation of a child or juvenile aged 8-12 years at death. The burial was unaccompanied.

1M344 (Fig 26) was located adjacent and parallel to, but not cutting, the outer edge of the inner ring gully in the south-east quadrant of the monument. The sub-rectangular cut, which was only 0.20 m deep, did not contain any human remains, but must have been a grave since it contained a Beaker (1M345 AA, Figure 27) standing almost upright in the centre of the eastern half.

1M273 (PL. IVA, Figure 25), located on the eastern perimeter of the enclosed area, contained three burials: in a primary position, skeleton 1M359 was of a small child aged 2-3 and probably female; the body was extended with the head to the south. This burial was sealed by a small quantity of chalk gravel, which may represent natural collapse of the grave walls, upon which lay the cremated remains of a female (samples 1M346-50) aged 25-30. This burial was in turn sealed by a thin layer of redeposited natural gravel upon which lay a second extended inhumation, skeleton 1M304, again that of a child laid out with the head to the south. The skeleton was probably that of a female, aged between 2.5-6 years. The shape of the grave both in plan and section, coupled with the layering demonstrable in the burials and the scaling deposits, indicate that the grave lay open between the insertion of the three burials, but that the time span between the insertion of the first and last burial must have been very short. An edge retouched knife (1M273) was recovered from the fill.

1M336 (Figure 28) was largest of all the grave cuts in this barrow, and must clearly be secondary to the inner ring gully through which it had been cut on its eastern side. The broad, shallow, egg-shaped pit was aligned east-west and contained the much decayed remains of an adult male skeleton laid out in a flexed position with the head to the east. This burial was accompanied by a crude edge-retouched flint knife (1M336 AA) placed just to the west of the feet.

1M338 (PL. IVB, Figure 26) was situated just inside the outer ditch 1m to the north of 1M273. The grave pit contained a tightly contracted skeleton of a child, probably female, aged 7-8. The long bones were disarticulated as a consequence of the tightly contracted position of the body. The body was accompanied by a perforated cow astragalus (1M365 AA, Figure 27), perhaps a toggle or a mace-head. Two fragments of cremated bone contained in the grave filling may be residual and indicate that this grave post-dates the nearby grave 1M273.

1M361 (Figure 25) This small grave pit, located to the north of 1M338 and just inside the outer ditch on the eastern side of the barrow, contained the fragmentary remains of the skeleton 1M363, an infant aged under I5 months. The burial, which was apparently flexed with the head to the south, was unaccompanied.

1M102, located on the southern side of the monument, was almost certainly a grave pit, given its sub-rectangular shape and size. Unfortunately all trace of any burial that it may have contained was subsequently removed during the cutting of the Period 5 ditch 1M902.

Four other features (1M52I, 1M370, 1M432, and 1M416) may also have been grave pits on the basis of their shape and size; unfortunately no bone or grave goods were recovered which could confirm this interpretation.

Just to the south-west of the barrow some human bone fragments were recovered during removal of the blown sands. No associated grave cut was located.

The Human Bones by Jean Dawes (M2/19-20)

Figure 26.

Barrow 1M: Graves 338, 344, 118.

Figure 27.

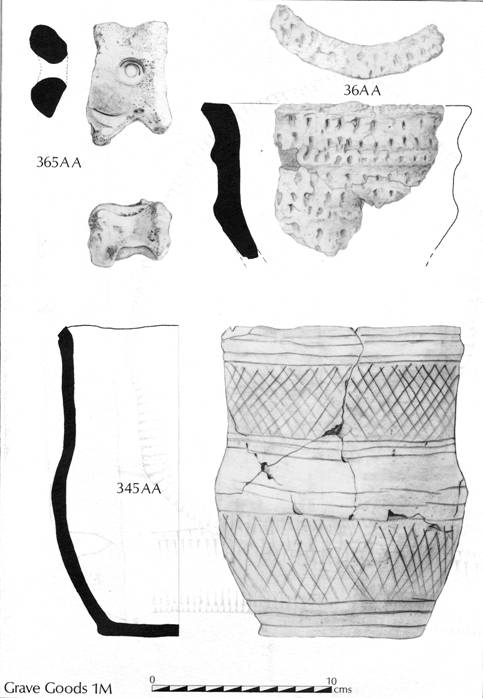

Barrow 1M: Grave Goods 365, 36, 345.

Figure 28.

Barrow 1M: Grave Plan 336.

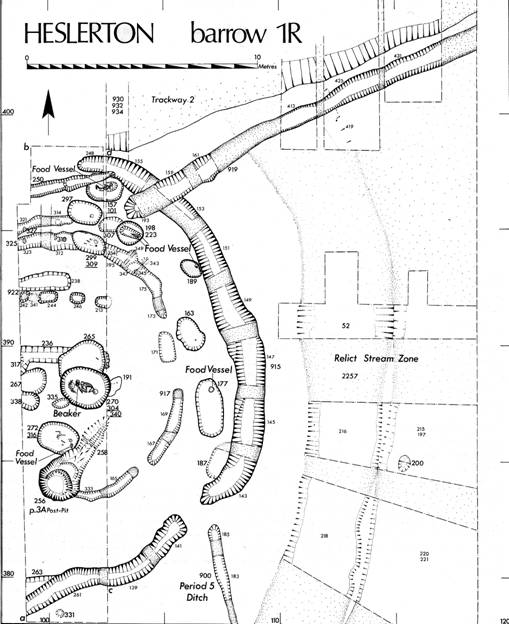

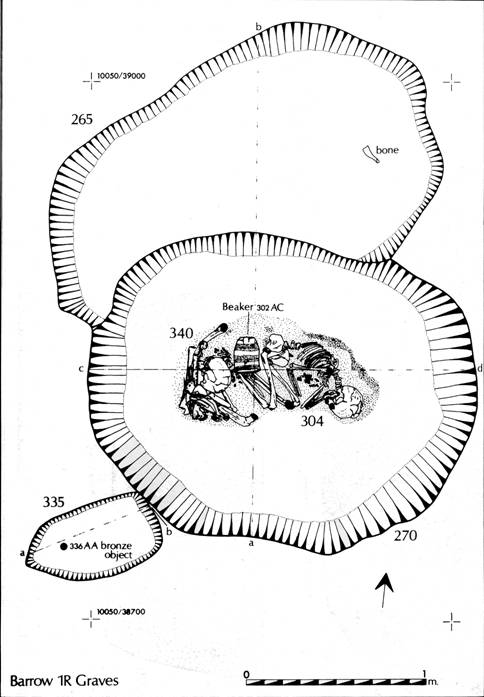

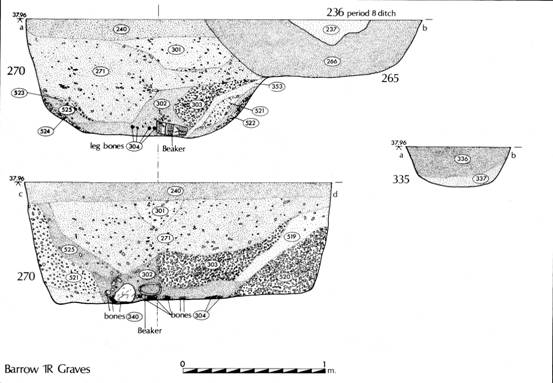

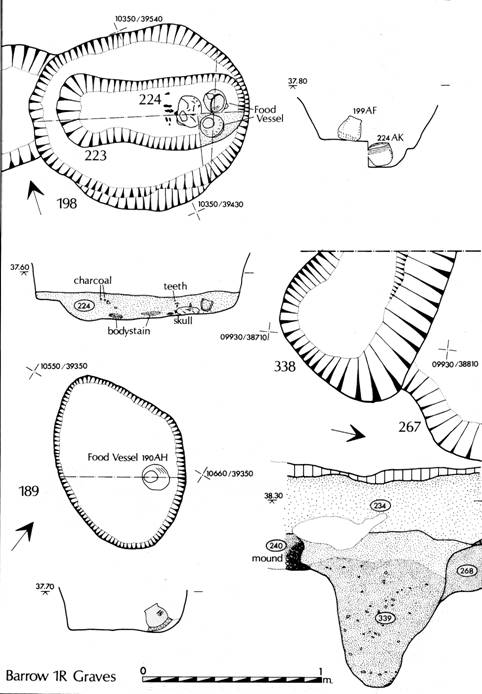

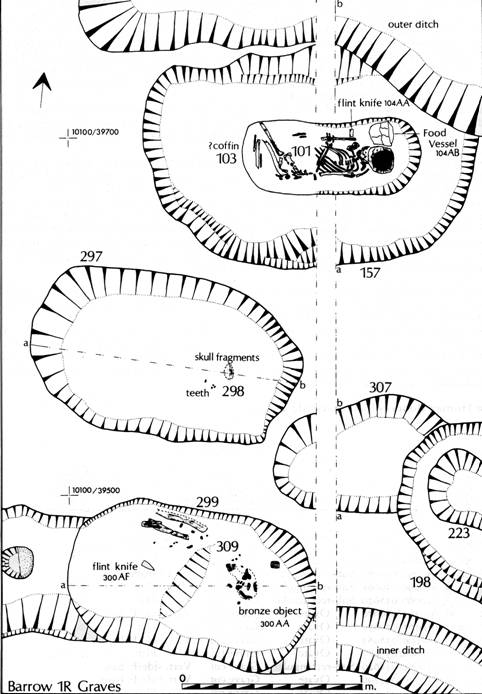

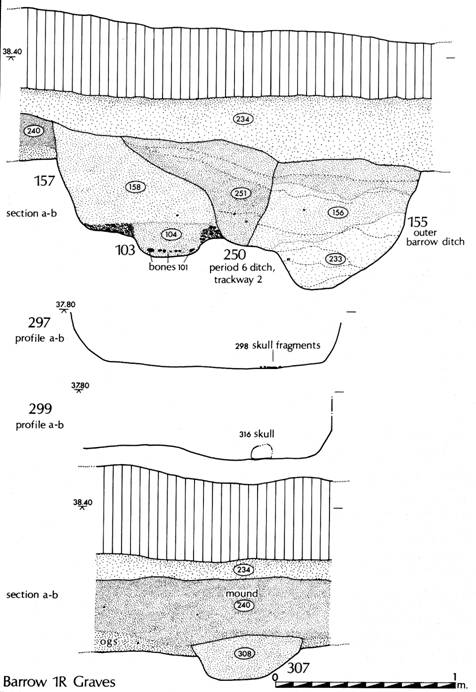

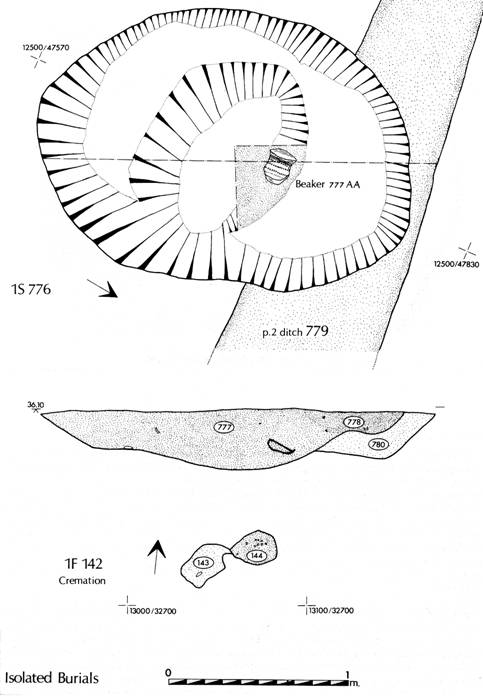

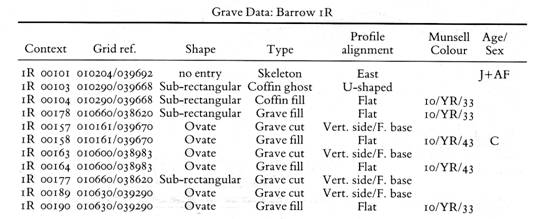

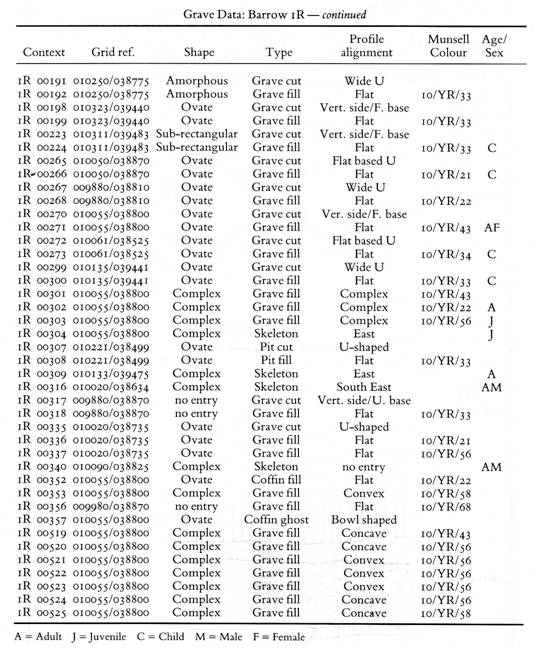

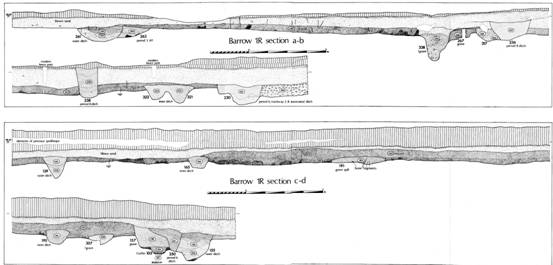

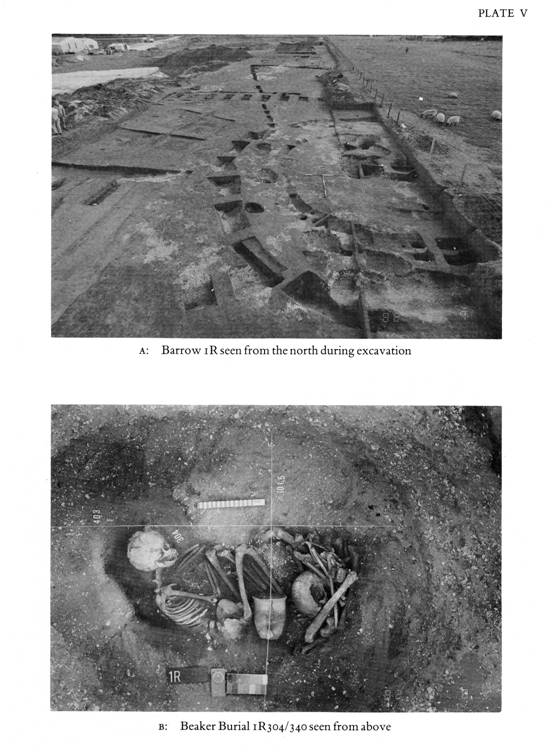

Barrow 1R (PL. VA, Figure 29)

This barrow, located on a slight platform in a bend on the western bank of the stream channel which separates it from barrow 1M 35m to the south-cast, extended beyond the limits of excavation to the west. It contained the highest density of burials in any of the barrows examined, the majority of which were accompanied. As with barrow 1M the central area was defined by a shallow ring gully, the outer ditch being much more substantial. Both the inner ring gully and the outer ditch were interrupted at a number of points. On the basis of the part examined the barrow appears to have covered an area up to 18m in diameter. Like the western side of barrow 1M, the mound seemed to have been partially eroded as a result of stream activity, the degree of preservation being generally lower than in barrow 1L. It is difficult to be certain as to the extent of this erosion since outside the central area, in which the surviving mound material was removed by hand, the area was stripped using a box scraper which removed part at least of the mound matrix.

Figure 29. Barrow 1R: Plan

The Mound (Section: Figure 75)

Little mound material survived and it was not possible to make any clear distinction between mound material and relict soils preserved as an old ground surface. A number of medieval or later post-holes, and two gullies which cut across the centre following an east-west alignment, indicated the presence of a late field boundary which also cut across the mound of barrow 1M and area 1N to the east. The grave cuts were quickly identified after removal of the first few spits of mound material in the central area, whilst in between the inner and outer ditches grave cuts could be isolated after the first cleaning of the area. A fragment of human bone was recovered from the mound matrix, 1R240.

The Ditches

In contrast to that in barrow 1M the inner ditch or gully, which enclosed an area measuring 11m in diameter, had a maximum depth of 0.4m, maximum breadth of 0.55m and ill-defined and weathered edges, particularly on the eastern and south-eastern sides; it was interrupted at four points in the area examined. Although it cut through the Period 3A post pit 1R256 on its southern side it could not be traced in the metre wide gap between this feature and the western limit of excavation. To the north, where it was matched by a second similar feature, the gully was both deeper and better defined but its scale indicated that it may have been no more than a marking-out ditch.

The outer ditch, which was interrupted both to the north and to the south-east, had a maximum breadth of 1.25m and a depth of up to 0.7m. On the southern side, where the ditch ran out of the site to the west, it was broad and shallow (0.55m). Although a shallow scoop ran in a westerly direction, as one might expect if the barrow were round, the main ditch alignment turned to follow a more southerly direction for reasons which could not be explained from evidence within the excavated area. A slightly inturned entrance on the south-east side of the monument left a 1m wide gap in the outer ditch, matched by a similar gap in the inner ring gully, which left a narrow causeway giving access to the centre of the enclosed area. To the north, the outer ditch stopped 2m short of the western limit of excavation and did not resume within the excavated area. The primary silts which filled the ditch to a depth of 0.25m contained no artefacts, above this a homogeneous stabilization layer contained a high proportion of aeolian material from which a small number of sherds and worked flints were recovered. On the northern side the ditch was cut by a ditch terminal relating to a Period 6 trackway which passed the northern edge of this barrow and barrow 1L to the east. A second apparently related ditch continued to define the line of the trackway running out of the area to the west, leaving a small entrance c. 2m wide.

The Graves

This barrow produced the largest assemblage of grave goods but bone preservation was still poor. The area as originally stripped did not include the central part of the monument. After the discovery of bone in a shallow scoop, 1R191, against the western limit of the excavation, the area was extended to include the central portion.

The grave sequence can in part be determined from the relationships between some of the grave pits. It is assumed, as in 1M, that the primary phase of the monument is represented by the shallow inner ring gully. A feature of this barrow not matched in the other examples was the widespread distribution, in the grave fills, of disarticulated bones additional to the principal interments, indicating the presence of a number of additional burials. There were no cremations present in the part examined. Not only was the frequency of grave goods higher here than in the other barrows of this group, but there was also a greater variety; three graves contained copper alloy objects.

Primary Burials

1R270 (PL. VB, Figs. 30, 31)

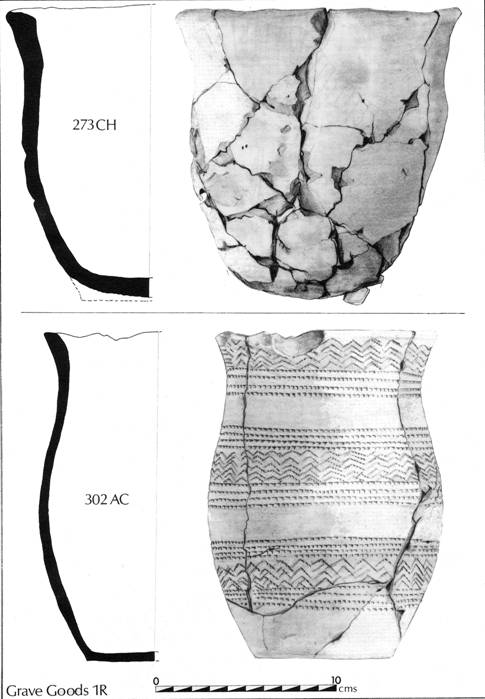

In contrast to the other barrows in this cemetery, this monument contained a single major primary grave in the centre. The sub-rectangular grave pit, located in the southern half of the central area, was the largest of the graves examined, measuring 2.15m long, 1.8m across and 0.84m deep. It had clearly been filled and then subsequently reopened prior to the construction of the mound, and contained one complete articulated and two partial disarticulated skeletons. The greater part of a mature adult male skeleton, 1R340, lay in the base of the grave; the bones had been carefully stacked at the western end of the pit. This burial had been disturbed when a second insertion, 1R304, had been laid in the base of the grave; the lack of small bones in the stack suggests that by the time of this disturbance the body had mostly or completely decayed, the larger bones being collected together having been exposed during the reopening of the grave pit. There was no indication that the primary burial had been accompanied by any grave goods. The later interment, that of a 12-14 year old of indeterminate sex, was laid out in a crouched position on its left side with the head to the east, a Beaker (1R302 AC, Figure 32) placed in the angle between the upper and lower legs. A thin and broken layer of charcoal above this burial indicated the presence of at least two very thin planks which appeared to have been laid immediately on top of the body but no further trace of a possible coffin was seen. The principal fill, 1R271, contained a number of further bone fragments: three vertebrae which appeared to have been articulated at the time of deposition, parts of the long bones, cranium, left clavicle, and right hand of an adult woman aged about 30 at death, distributed randomly within the fill. Immediately sealing the burial 1R304, further fragments of human bone were found mixed in the fill 1R302. This grave was entirely scaled by the mound.

1R265 (Figs. 30 and 31)

This shallow flat based grave pit, which cut both the barrow mound and the primary grave 1R270, contained some tiny fragments of bone and a mandible with teeth indicating an age at death of between 10 and 17 years. The bone fragments were insufficient for sexing the body, which was accompanied by a flint flake (1R266 AF) and a tiny fragment of a copper alloy pin (1R266 AD).

Figure 30. Barrow 1R: Grave plans: 270, 265, 335

1R335 (Figs. 30 and 31)

This was a very small ovate pit which cut the primary grave 1R270 on its south-western side. The pit, which if a grave could only have held an infant burial, contained a small copper alloy button-like object (1R336 AA). No bone or other artefacts indicating the function of the pit were recovered.

Figure 31.

Barrow 1R: Grave sections: 270, 265, 335

Figure 32.

Barrow 1R: Pots 302, 273.

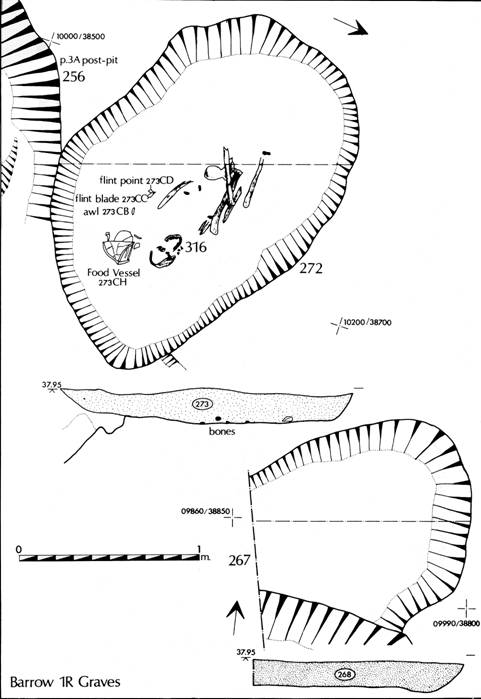

1R272 (Figure 33)

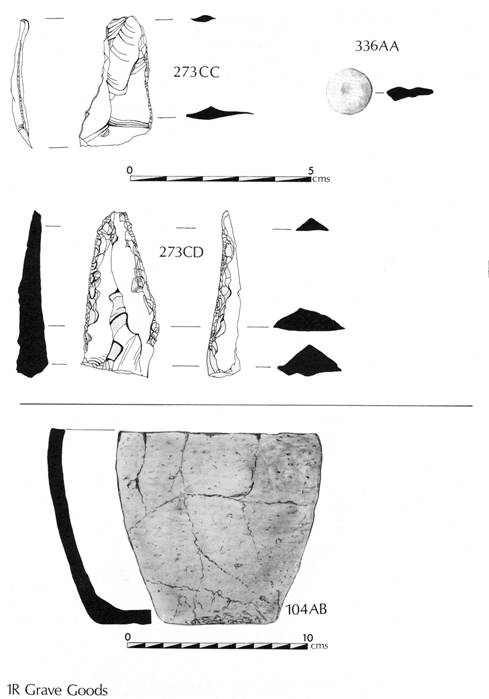

A sub-rectangular grave pit located to the south of 1R270, cut through the Period 3A post-pit 1R256 and was sealed by the mound. It contained the badly preserved skeleton of an adult male aged more than 35 and possibly even 45. The surviving long bone fragments suggested that the burial had been laid out in a crouched position with the head to the east. An undecorated Food Vessel (1R273 CH, Figure 32) had been placed just behind and to the left of the cranium. A worked flint blade and a point (1R273 CC and CD, Figure 34) and a copper alloy awl (CB) were placed at the left side. As in grave 2C40, Barrow Cemetery 2, they may have been contained in a small bag. Also contained within the fill 1R273 were bone fragments of an infant.

Copper alloy awl or pin: AM No. 832971 SEM Stub A406 Ref. No. WH 82 R273 CB

Composition of metal - the object has a gold rich layer on a corroded core. It may have been gold plated bronze. Alternatively it may have been debased gold, possibly with an enriched surface, in which case its present condition would be due to burial effects (P. T. Wilthew, AML Report 4255).

Associated wood: possibly Alnus sp or Corylus sp. (Jacqui Watson, AML Report 4255).

Two further possible grave cuts were isolated within the central area, 1R267 and 1R338, neither of which contained any bone; both extended beyond the limit of excavation to the west.

Figure 33.

Barrow 1R: Grave plans: 272, 267.

Figure 34. Barrow 1R: Grave goods (flints).

Secondary Burials

The narrow space between the inner ring gully and the outer ditch contained seven definite and one possible grave pits, four of which were in a group on the northern side of the barrow.

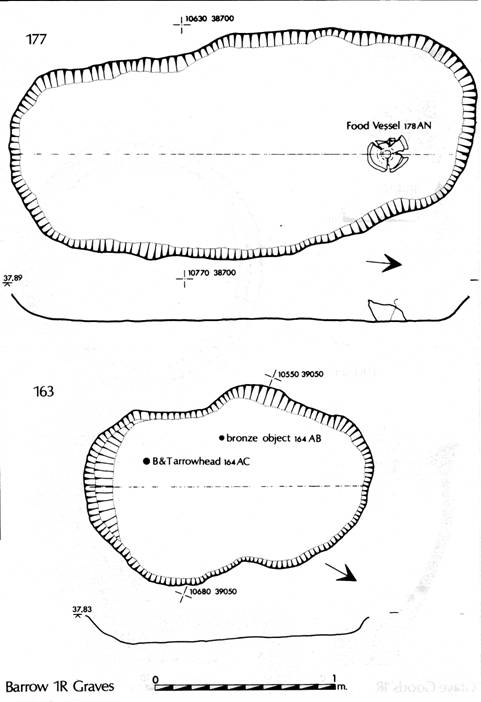

1R177 (Figure 36)

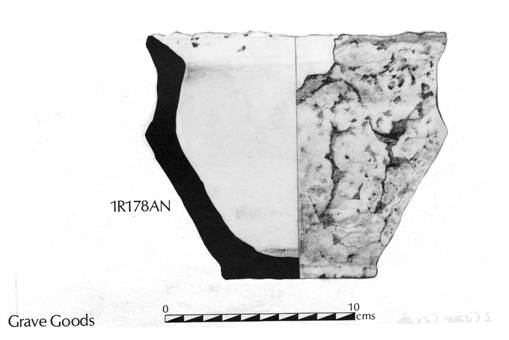

The grave was aligned north-south, placed midway between the two ditches on the eastern side of the monument; it was very shallow and contained no surviving bone or body staining. At the northern end on the eastern side it contained the very fragmented remains of a Food Vessel (1R178 AN, Figure 35) standing upright in the base of the grave. The pot, which was undecorated, was badly crushed and distorted.

Figure 35.

Barrow 1R: Grave plans: 163, 177.

Figure 36. Barrow 1R: Grave plans: 163, 177.

1R163 (Figure 36)

1R163 lay to the north of 1R177, and was a shallow sub-rectangular cut; again containing no surviving bone or body staining. Its function was indicated by the presence of a barbed and tanged arrowhead

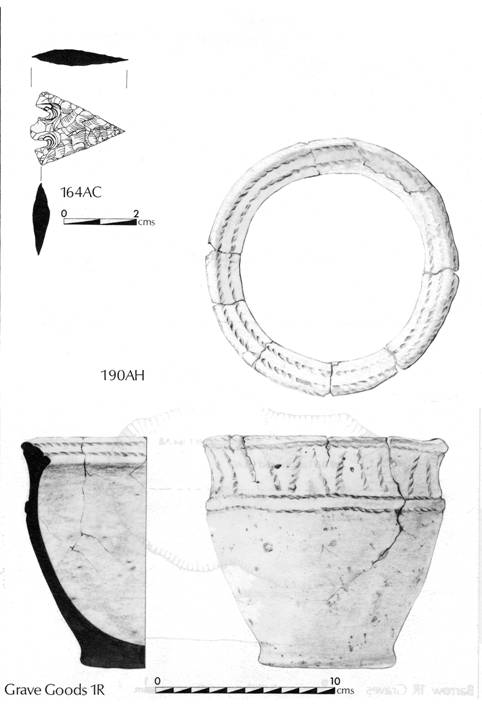

(1R164 AC, Figure 37) and a small fragment of copper alloy (1R164 AB).

Figure 37. Barrow 1R: Grave Goods 190 (pot) 164 (arrowhead).

1R189 (Figure 38)

A small ovate grave, 1R189 was situated adjacent to the outer ditch on the north-east side of the barrow and contained an inverted Food Vessel (1R190 AH, Figure 37) placed against the eastern side of the cut. The size of the cut suggests that though no bones were recovered it probably contained the burial of a child.

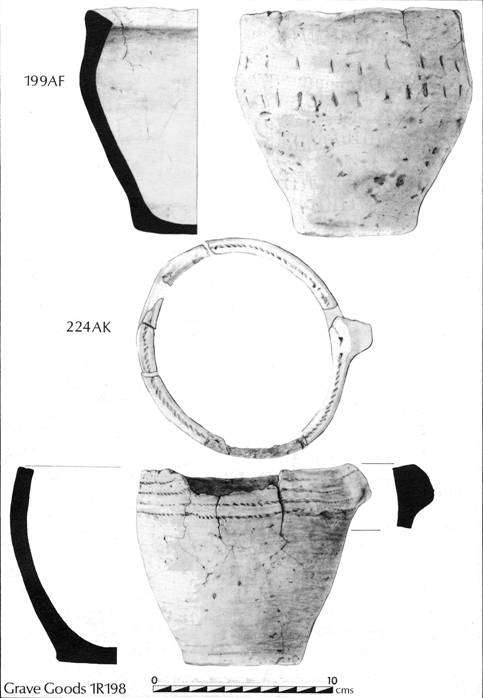

1R198/223 (Figure 38).

1R198 was a small ovate cut on the northern side of the barrow, located between the inner ring gully and the butt end of the period 6 ditch 1R919, which contained a second smaller sub-rectangular cut 1R223 in the base. This lower cut. which was well defined, appeared to represent a primary grave, the top of which had subsequently been entirely cut away by 1R198. It contained fragments of bone, 1R224, including most of the skull, of a small child aged 3-6 years. The burial was accompanied by an upright Food Vessel (1R224 AK, Figure 39) positioned at the eastern end of the cut. 1R198 above, contained a few small fragments of bone including teeth apparently derived from the lower feature, no other bone was recovered. It did however contain an inverted Food Vessel (1R199 AF, Figure 39) positioned above and slightly to the south of the vessel in 1R223 below. It is arguable that this cut could have contained a child burial and that the upper grave was cut to the level of the lower Food Vessel at which point the second burial was inserted causing only slight disturbance of the grave below. The generally poor levels of bone preservation mean that it is impossible to confirm or discount the suggested sequence.

Figure 38.

Barrow 1R: Grave plans: 198, 338, 189.

Figure 39. Barrow 1R: Pots 199, 224.

1R299 (Figs. 40 and 41)

This was a shallow trapezoidal cut located to the north of the central area which, since it cut through the inner ring gully, must represent a secondary grave; it contained the fragmentary remains of the skull and long bones of an adult male, 1R309, aged20-30. The position of the surviving bones indicated that the burial had been laid in a crouched or contracted position with the head to the cast. The burial was accompanied by an edge-retouched flint knife (1R300 AF, Figure 34) and a bronze object (1R300 AA). The grave fill, 1R300, also contained a number of very small bone fragments possibly from an infant or child; these may be residual and derive from the disturbance of 1R223 or 1R298, both of which are nearby.

1R297 (Figs. 40 and 41)

Located on the northern side of the monument where it cut through the butt end of the secondary inner ring gully, was a shallow sub-rectangular grave. It contained poorly preserved bones of an infant aged 2-4, 1R298, in which only the skull was substantially preserved. The burial was unaccompanied.

Figure 40. Barrow 1R: Grave plans: 297, 157, 307, 198, 299.

1R157 (Figs. 40 and 41)

1R157 was cut through the inner edge of the northern butt end of the outer barrow ditch, and had in turn been cut along its northern edge by the butt end of a Period 6 trackway ditch. The sub-rectangular grave pit contained the flexed burial, 1R101, of a child aged 7-9. The body, placed with the head to the cast, was accompanied by a small undecorated Food Vessel (1R104 AB, Figure 34) lying on its side in the angle between the left shoulder and the cranium, and a worked flint (1R104 AA, Figure 34) placed adjacent to the pot. The skeleton was contained by a distinctive fill with a 'U-shaped' profile indicating that the body had been contained in a small coffin, possibly tree-trunk type, defined by the backfill of natural sand and gravel. Also contained within the backfill were a number of bone fragments from an adult, probably a female.

Figure 41. Barrow 1R: Grave sections 297.

Isolated Burials and Flat Graves

1F143 (Figure 43)

A small quantity of calcined bone which included human fragments, was located on the eastern edge of area 1F in a plough-damaged area. The deposit was so truncated that detailed interpretation was impossible.

1S776 (Figure 43)

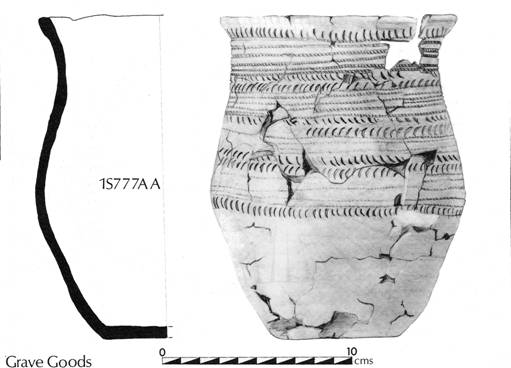

The earliest of all the Beaker graves was located 75m to the north of Barrow 1M. The large ovate grave, which had cut through the Period 2 ditch 1S779, contained no surviving bone but did contain a small Beaker, 1S777 AA (Figure 42), which itself contained a small flint blade. There was no evidence of any enclosing ditch or associated mound with this burial and it must be viewed as an indicator of flat cemetery traditions.

Figure 42.

Beaker 1S777

Figure 43. Plans of IS776 1F142

The Human Bones by Jean Dawes (M2/2 I-22)

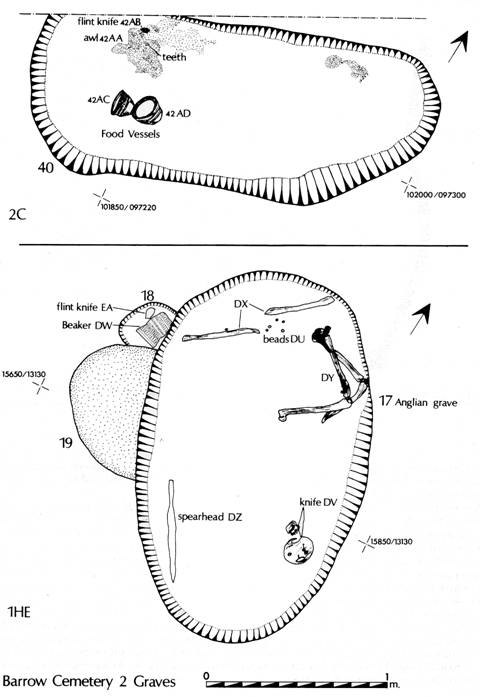

BARROW CEMETERY 2

In contrast to the central part of Site 1, areas 1A, 1HE and parts of the areas examined on Site 2 had been subjected to erosion by the plough, possibly coupled with wind erosion. The barrow cemetery postulated in this area has since been confirmed by excavation.

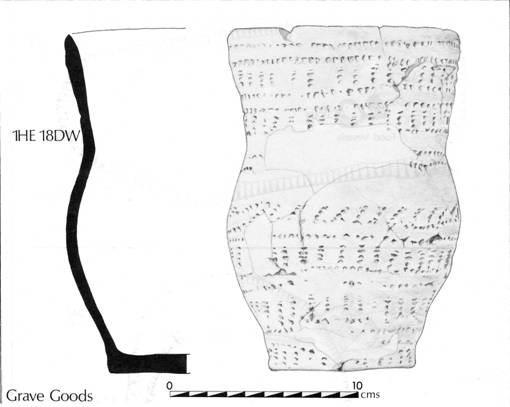

During the salvage excavation of 1HE by Dent, a Beaker burial 1HE18 DW (Figure 44), was located which had been subsequently cut through twice by Period 7 burials 1HE10 and 1HEI7. This relationship, together with the discontinuity of the Period 6 ditches in area A, implies the presence of some sort of mound associated with the Beaker burial even though the scale of it must have been very small. A barrow cemetery postulated in this area has since been confirmed. Five metres to the south of this feature a quantity of cremated bone associated with 6 sherds of Bronze Age pottery were located at the base of the windblown sand deposits, perhaps indicating the presence of a further burial from this period.

Figure 44. Beaker 1HE18

Fifty metres to the west-south-west of burial 1HE18, a ring gully 1A21 enclosing an area c. 8 m in diameter, was cut by a single burial, 1A18. The ditch, which extended beyond the limits of excavation, survived to its greatest depth against the field boundary which marked the southern edge of the site. The ditch fill, a homogeneous sand, displayed no indication that the ditch had been structural and contained no domestic debris besides a few flint flakes. Burial 1A18, in a prone position with the hands possibly tied together beneath the pelvis, was unaccompanied, and appeared to have been buried alive. The bone was unusually well-preserved and has a single radiocarbon date of HAR6517 2280 ± 80bp (330bc).

Its presence indicates a continuity of function that might already be suggested from the incidence of the early Bronze Age and Anglian cemeteries on the same ground; furthermore, it demonstrates the potential of radiocarbon dating for the identification of periods of activity that would otherwise have remained unnoticed. Detailed discussion of this burial will be included in the second report, on completion of excavation on Cemetery 2.

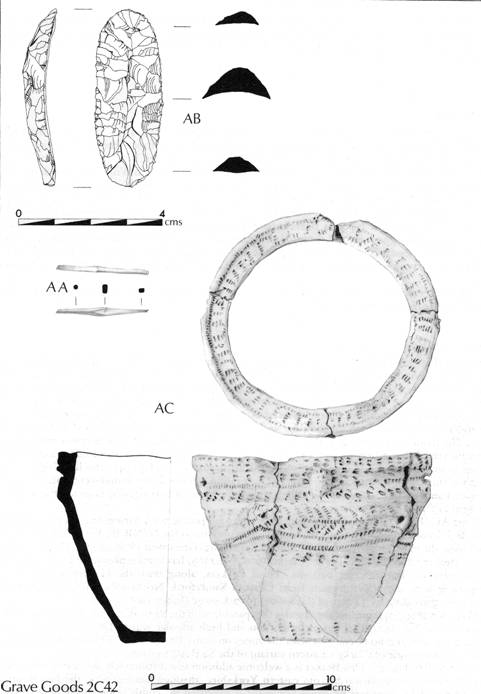

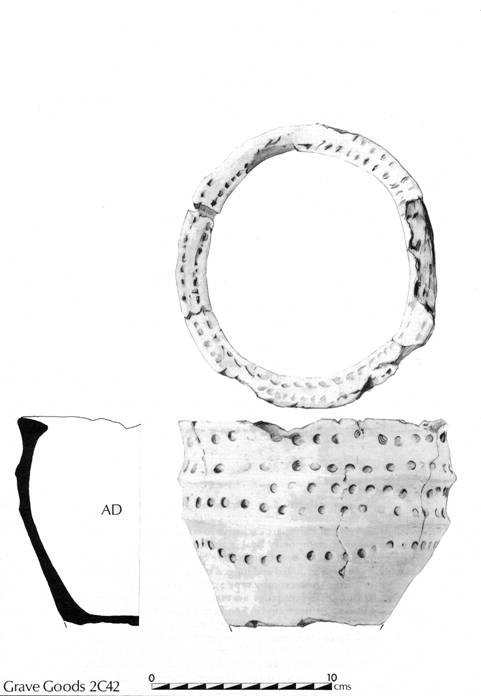

Fifty metres to the south on Site 2, a single grave 2C40 (Figure 45) indicated the presence of a further barrow. This grave, cut to a depth of 0.45m was aligned east-west and contained no surviving bones. Fragments of tooth enamel were recovered from a patch of ill-defined body staining, 2C42, and indicated that the burial had lain with the head to the west. The burial was accompanied by two small Food Vessels (2C42 AC, Figure 46; and AD, Figure 47), a plano-convex flint knife (2C42 AB, Figure 46) and a copper alloy awl (2C42 AA, Figure 46). They were all located on the northern side of the grave cut at the western end, where the juxtaposition of the awl and knife indicate that they had been contained in a bag. Thirty-five metres to the east of this grave, part of a ring gully was located. Excavation currently in progress has revealed that 2C40 lay just beyond the northern side of a barrow which has yet to be excavated, whilst the ring gully discovered in 1981 was part of a barrow ditch within which two Food Vessel inhumations, a Food Vessel accompanying a cremation, and a second unaccompanied cremation were discovered in 1985. Excavation of this area, 2BA, is currently in progress and will be discussed in full together with the Period 7 cemetery in the second report. At least two barrows in this area remain to be excavated during 1986.

Figure 45. Plans 1HE18 2C40

Human Bones by Jean Dawes (M2/22)

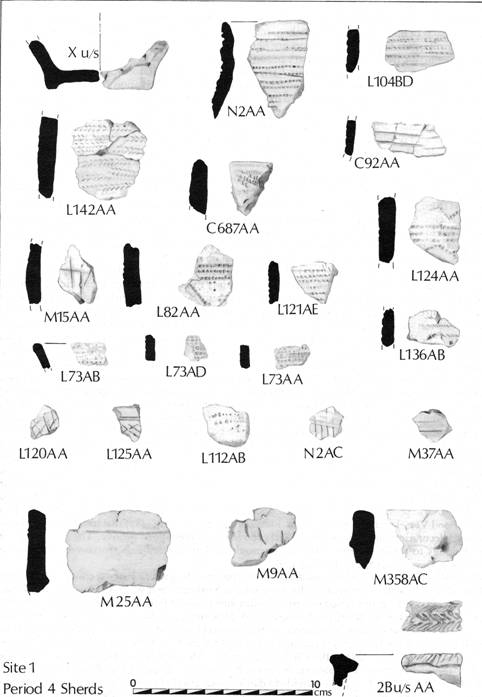

THE POTTERY by T. G. Manby (see M2/23-49)

The sherd material and accessory vessels for the burial series at Heslerton is an extensive one.

Description of the sherd material and the individual pots occurs under the site areas in the microfiche and introductory comments are provided below. The bibliography has been included in the microfiche.

The Beakers

The Beaker pottery comprises both scattered sherds derived from occupational activity and complete vessels accompanying burials. This concentration on the sands at the foot of the Wolds has a parallel in the concentration to the east around the spring head at Staxton Corner. This consists of burials, some with Beakers of N/NR (Brewster 1951), S1 and S4 types (Stead 1959) in Willerby parish and another N/NR in Flixton (Dunning 1933). AOC Beaker sherds were associated with possible post-holes at Sammy Ridings Pit, Flixton and Granger's Pit, Staxton (pers. comm. T. C. M. Brewster), sherds from Sherburn (Roman Malton Museum Collection) and the N2 Beaker from Scampston (Clarke 1970, No. 1381, Figure 501). The types of Beakers from Heslerton and Staxton Corner indicate activity at these localities throughout the full chronological ranges of these vessels. Apart from the Step 3 Beaker (1S777 AA) the vessels closely parallel in profile and decoration Beakers from the Yorkshire Wolds and fit in to the typological scheme for the Yorkshire area (Lanting and van der Waals 1972, 39-40, Figure 3).

Small Beaker sherds were well scattered in the mound and ditch siltings of Barrow 1L and a small number were present in Barrow 1M.

The Accessory Vessels -Comments

IS777 AA (Figure 42)

This is a most interesting vessel with unique features for the Yorkshire Beaker area. Its full reconstruction would modify thoughts on its parallels and affinities; an immediate consideration was to compare the decorative motifs and layout to the PFB vessels of the Netherlands Beaker series where the absence of ornament below the shoulder is a characteristic aspect. The Heslerton vessel lacks the moulded base and is comparable with the South Cave Beaker that has horizontal cord lines down to the shoulder with a fringe of diagonal strokes below (Clarke 1970, No. 1259). The Raindale, Pickering Beaker (Clarke 1970, 1362) has horizontal comb lines confined to the upper two thirds but differs in profile from our vessel. Also to be taken into consideration must be a Beaker from Huggate and Warter Barrow 264 (Mortimer 1905, 317, Figure 945); this has a high rounded shoulder, short neck and outcurving rim. The decoration extends down to mid-height and consists of alternate bands of horizontal lines and herringbone; a zone of herringbone is inside the rim (Hull Museum 215.42).

Figure 46. Grave

goods 2C42AC

Figure 47. Grave goods 2C42AD

1R302 AC (Figure 32)

This vessel is distinctive in its tall profile with flaring rim. Its best parallel in shape and decorative motif of zones of vertical herringbone is the N/NR Beaker (Clarke 1970, No. 1369) from the massive shaft grave of Rudston Barrow 62 (Greenwell 1877, 253-57; Pacitto 1972). A second Beaker from the same grave (Clarke 1970, No. 1368) has a similar profile and arrangement of decorative zones but different patterns. These Beakers, along with the Heslerton example, are comparable with the N/NR vessels from Chatton Sandyford, Northumberland, post-dating the stake-holes providing a C4 date of (GaK-800) 1670 ± 50 bc (Jobey 1968, 5-30).

1M345 AA (Figure 27)

In profile the vessel is comparable with the S4 Beaker from Rudston Barrow 63 (Clarke 1970, No. 1373) that has a rim cordon and high angular waist. The deep bands of cross-hatching on neck and body contrast with the zones on many late Beakers. The cylindrical neck and cordon are diagnostic of Clarke's Eastern variant of the S2 Beaker group.

1L20 AA-BB (Figure 19)

This Beaker is a welcome addition to a distinctively decorated series of late Beakers distributed southwards from eastern Yorkshire, through Lincolnshire, the Fen Basin and East Anglia. The characteristic panel ornament is executed by comb impressions or incision on normal Beakers and a wider range of shapes with handles. The motifs are mixed with horizontal zones, and the panels are simple lozenges and elongated hexagons (Clarke 1970). In terms of decoration this Beaker is closely comparable with S4 Beakers from:

Staxton (Clarke 1970, No. 1392) Incised. Vale of Pickering

Acklam 214 (Clarke 1970, No. 1211) Incised. Wolds

Folkton 242 (Clarke 1970, No. 1280) Comb. Wolds

Octon (Brewster forthcoming) Comb. Wolds

Handled Pickering (Clarke 1970, No. 1360) Incised. Moors

All these display cross hatched hexagonal panels; at Staxton, Acklam, and Pickering in combination with cross-hatched horizontal bands. Thus in terms of the sole use of hexagons and their interlocking layout to produce the reserved structure in between, it is the Folkton and Octon Beakers that are indicative of the Heslerton Beaker. The laying out of the pattern would have required experience and, an understanding of mathematical proportions.

Figure 48. Beaker sherds.

The Food Vessels

The Heslerton site is notable for the number of Food Vessels recovered. Previously the only vessel known came from Kirby Misperton (Yorkshire Museum 1189.47) in the middle of the Vale and the sherds from Granger's Pit, Staxton (T. C. M. Brewster collection) at the foot of the Wolds. Eastern, Yorkshire has the greatest concentration of Food Vessel finds in the British Isles, totalling 355 recorded vessels, 236 coming from the Wolds and 101 from the North York Moors. Not included in these figures are Enlarged Food Vessel urns and the miniature Food Vessels of the accessory cup series. The Food Vessels are essentially known as accessory vessels with burials, the majority inhumations, and only rarely did they contain cremated bones when associated with the minority cremation rite. The vessels are almost entirely of the Yorkshire Vase series, first defined by Abercromby into six types by shape with six sub-types and the exotic handled and footed vessels (Abercromby 1912, I, 93-94). It was noticed that all the types were contemporary; a conclusion confirmed by Mrs M. Chitty's study of Food Vessels from Yorkshire (Kitson-Clark 1937). Before the advent of C14 dating the only avenues available for the interpretation of the vast array of pottery were typology and associations, both ritual and material. A regional study of the Peak District Food Vessels in comparison with those of Yorkshire produced an evolved development classification that reduced Abercromby's types to five, each divided into stages, and three variant types (Manby 1957). Regional preferences in shape and decoration are demonstrable and offer a profitable field of research. The national approach to Food Vessel classification extended Abercromby's Groupings into:

1. Yorkshire Vases

2. Southern English Food Vessels

3. Irish Bowls

4. Irish Vases

These Groupings overlap in the British Isles (ApSimon 1958) and the study of their cultural associations (Simpson 1968) demonstrates that pure cultural assemblages are not present for any Grouping. Only plano-convex flint knives are exclusive to Food Vessels; all other flint, stone, jet, and bronze types were shared with contemporary Beaker and Urn ceramic associations.

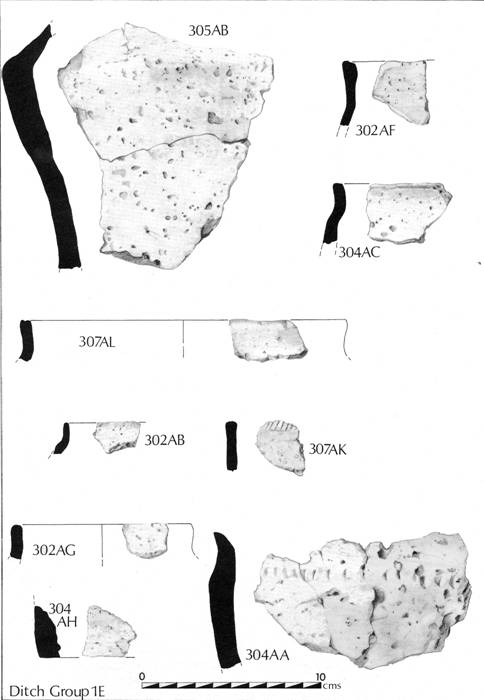

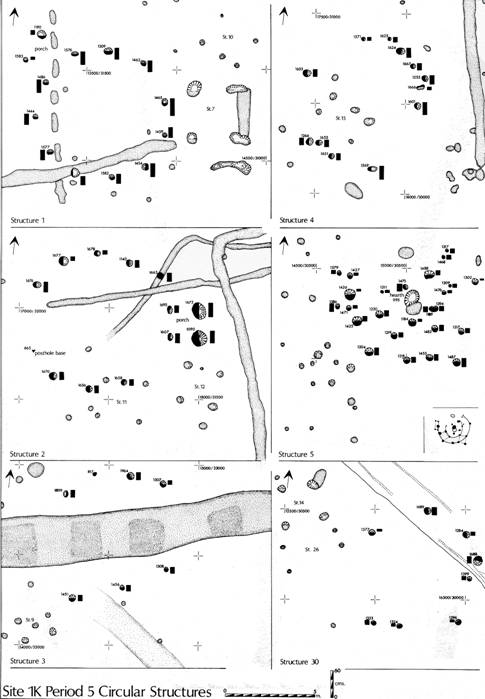

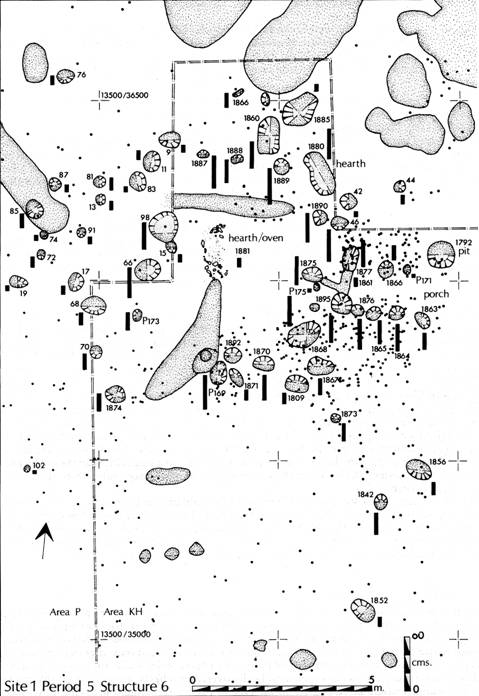

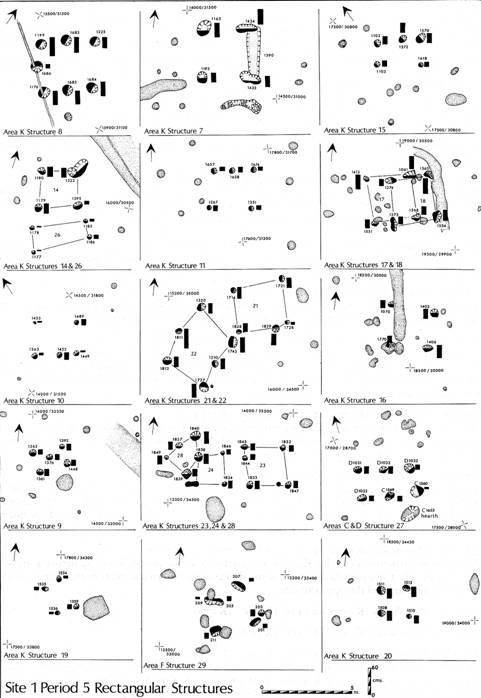

The Vase series of Food Vessels in Great Britain have been given descriptive groupings based on shape; Bipartite including shoulder grooved and lugged types (Abercromby types 1 and 3); a Ridged Group, especially tripartite forms (Abercromby type 2); Bucket Group (Abercromby types 4 and 5) (Burgess 1980, 86-89). Within these groupings northern and southern sub-groups are also recognisable. The lugged Food Vessels are not found in Southern England and there is a tendency to refer to these as 'Yorkshire type'; however they are one of the three basic form of the Eastern Yorkshire regional distribution. The regional characteristics of Food Vessels have been demonstrated for Wales (Savory 1957), the Peak District (Manby 1957), Northumberland and Durham (Gibson 1978), and South-western Scotland (Simpson 1965). The sheer number of Food Vessels from Yorkshire has deterred corpus publication but the characteristics of this concentration and other regional groups in Northern England and Southern Scotland has recently been summarised (Pierpoint 1980, 63-123). A social approach to the study of Food Vessels and their burial associations was developed by Pierpoint that also considered the character and quality of the vessels. The traditional typological concept of degeneration of the shape, from fine to coarse, was rightly contrasted with the existence of higher quality vessels of finer fabric and modelling, intensive decoration, and novel features, being the work of specialist potters. Such quality pieces are likely to have been produced for significant interments and are distinctive from ordinary pottery production.